To mark Ovarian Cancer Awareness Month, Professor Christina Fotopoulou, Chair in Gynaecological Cancer Surgery and Professor of Gynaecological Cancer in the Department of Surgery and Cancer, and consultant gynaecological oncologist at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust—reflects on Imperial’s recent breakthroughs in the field. Delving into Imperial’s pioneering efforts to enhance diagnosis, treatment, and understanding of this complex disease, Christina also sheds light on some of the unique challenges faced.

[Updated September 2025]

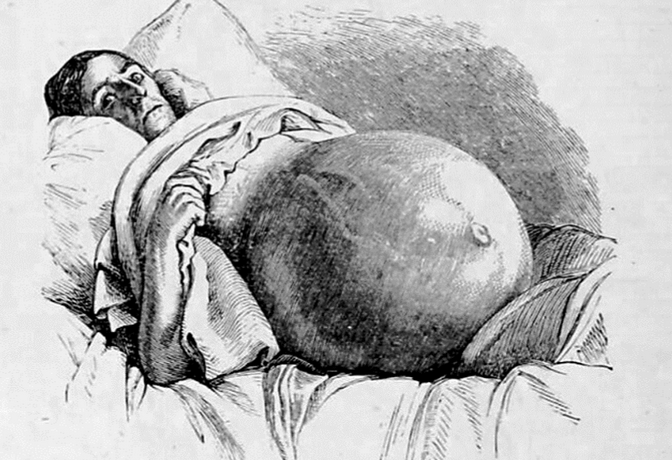

The time has come once again for Ovarian Cancer Awareness Month in the UK. This is our annual opportunity to shine a spotlight on ovarian cancer and increase awareness of a disease that has been a significant challenge for women for centuries (see fig. 1).

Imperial and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust have made significant strides towards improving the diagnosis and management of ovarian cancer for many years, and there is even long-term hope of a cure in the future. Through pioneering systemic and surgical therapeutic strategies and conducting ground-breaking research, the Imperial clinicians and researchers have established themselves as global leaders in the field of gynaecological cancer.

We now are very happy to announce our partnership with a large european consortium to advance novel approaches for risk assessment and early detection of this challenging disease, with the ultimate aim of improving outcomes of our patients. The European Union’s European Health and Digital Executive Agency (HADEA), has launched DISARM, a Horizon Europe Innovation Action project that brings together 28 partners from 12 countries, including the UK and Canada. The project officially launched on 1 September 2025 and will run for four years with €13.2 million in funding under the EU Mission on Cancer. Imperial College London is a core partner in the consortium. The project is led at Imperial by Professor Christina Fotopoulou, Principal Investigator, with Dr Paula Cunnea, Dr Jonathan Krell and Professor Iain McNeish as co-investigators, all based in the Department of Surgery and Cancer.

The fight continues for better care, improved quality of life and increased survival rates for patients.

But what makes ovarian cancer unique among women’s cancers? The dedicated efforts of the gynaecological oncology community, combined with the specific tumour biology of this disease, mean that this is perhaps the only diagnosis where a cancer that has spread throughout the abdomen can still be effectively operated and treated—sometimes leading to long-term remission. Many patients affected by the disease can live for years following treatment.

Simultaneously, advancements in systemic treatments, including the use of novel maintenance therapies (treatment which offers patients both traditional chemotherapy and a course of newly developed drugs that are taken even after chemo ends ) alongside traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy, tailored to both the patient’s genetic profile and the tumour characteristics, have led to unprecedented survival rates, even for patients with high tumour burden.

In addition to our researcher’s skills and expertise, Imperial’s infrastructure and settings are key to optimising conditions of care. Finessing and tailoring the notion of prehabilitation—getting ready for cancer care—to our patients is essential, all under the umbrella of a holistic and individualised approach. These aspects are best achieved in environments like those at Imperial. What further distinguishes our setting as unique is the close interlink between clinic and research; hospital and university. This collaboration aims to better understand not only how diseases evolve and progress but also their unique characteristics in each patient, integrating tumour biology into the treatment decision-making process.

Our centre has now become a supraregional NHS and private treatment cancer centre for ovarian cancer treatment, attracting patients from all over the UK and beyond. This has brought unique advantages not only at the patient level but also in research. These advantages include biobanking, the collection of rare presentations of the disease, and the centralisation of knowledge and expert qualities that only a few centres in the world can match.

In a disease where every conventional screening approach has so far failed to demonstrate efficacy, the actual treatment of the condition upon diagnosis is key to success. Moreover, the university’s bioengineering department in South Kensington offers us clinicians, completely out-of-the-box opportunities to approach early diagnosis through novel technology. The developments open revolutionary and promising insights into the disease, providing more hope that early diagnosis will no longer remain as elusive as it is now.

Concurrently, multiple new avenues are opening across various many aspects of the diagnosis, management, and follow up of treating ovarian cancer. I am hopeful that we will keep reporting ground-breaking research, with the Imperial team being at the centre of events.