Professor John Tregoning, Professor of Vaccine Immunology in the Department of Infectious Disease, explores the legacy of Sir Alexander Fleming and the urgent fight against antimicrobial resistance. From the historic discovery of penicillin at St Mary’s Medical School to the ambitious Fleming Initiative, Professor Tregoning discusses how a groundbreaking new centre aims to tackle one of the greatest challenges in modern medicine.

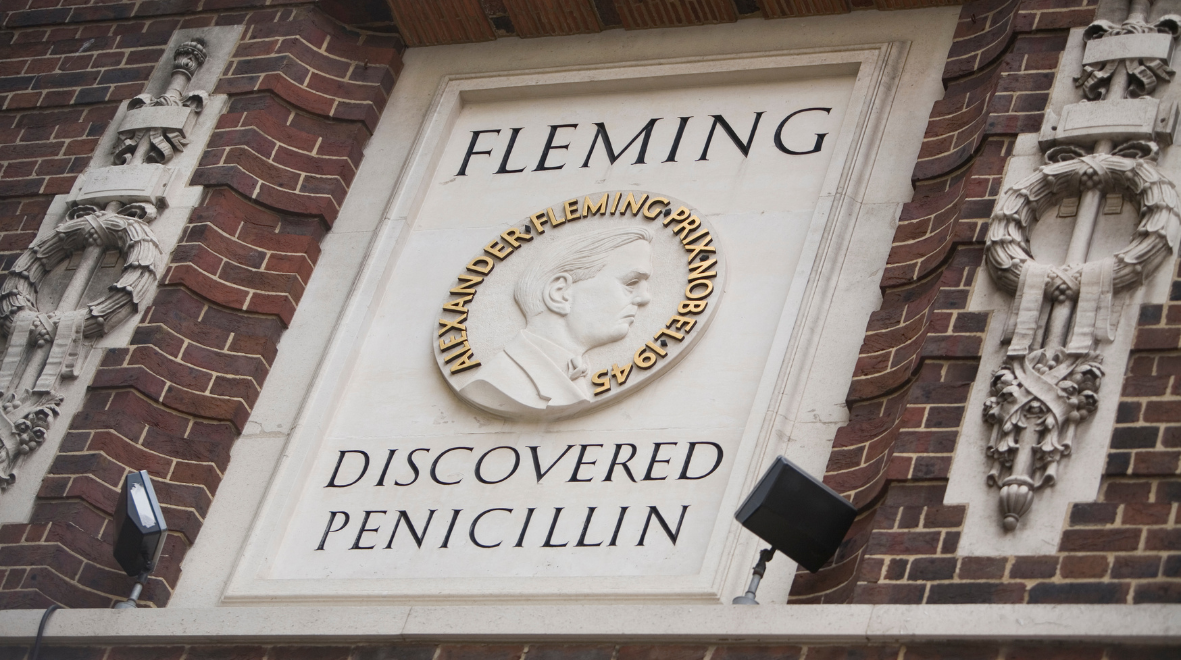

If you were watching the Royal Institution (RI) Christmas Lectures with Dr Chris van Tulleken, you will have seen two plates of food disintegrate into a mushy goo. This was filmed at the St Mary’s Medical School Building in Paddington, London. In fact, it was probably the last ever experiment done in this hallowed building. In some ways it seems appropriate that it involved mould. St Mary’s will always be famous as the site of where Sir Alexander Fleming performed his breakthrough studies. Or as he modestly put it: ‘revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic’.

The story of Fleming and his contaminated plates has often been retold. Basically, his lab was a bit of a dive; he hadn’t tidied up before going on his summer holiday and he got contamination on his bacterial growth studies. For some reason best known to him, rather than saying ‘oh no, I’ve ruined my experiment’, he said, ‘that’s curious’, and isolated the mould juice that could kill bacteria. The story goes on to tell how the mould spores came from the Fountains Abbey pub across the road. But having a dirty lab alone doesn’t, unfortunately, guarantee you Nobel Prizes – if it did, I could easily rank my PhD students in order of likelihood of winning one. Fleming’s brilliance lay in seeing the breakthrough in an otherwise unplanned situation.

The fungi contaminating Fleming’s plates was a Penicillium, from which he named the active compound penicillin. Nothing much happened between the initial discovery in 1928 and 1940, when Howard Florey and Ernst Chain (latterly of Imperial), while working at Oxford University, developed a process for extracting penicillin from fungal broth, for which they shared the 1945 Nobel Prize with Fleming. Antibiotics have dramatically changed the face of modern medicine. Many bacterial infections that were once fatal can now be managed.

However, there is a looming shadow on the horizon. We are seeing a huge rise in antibiotic resistance, which is not as it might sound: it does not mean resistance of people to antibiotics, but the ability of certain bacteria to survive antibiotic treatment. Drug resistance (sometimes called antimicrobial resistance or ‘AMR’) is a serious problem: each year half a million people die around the world because of resistant bacteria. The problem isn’t necessarily a new one, Fleming predicted the emergence of antibiotic resistance in 1945. But it is gathering pace. Not just for bacterial infections, but also for fungal ones too.

But there is room for optimism. A new hope is rising phoenix-like (or emerging penicillium-like, to keep the microbial analogy) at St Mary’s. The Fleming Initiative, established jointly by Imperial College London and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, is bringing together researchers, policymakers, clinicians, behavioural experts, commercial partners and the public to find solutions to antimicrobial resistance at a global scale. It has already gained the support of the UK government, including founding partner GSK. It will drive the creation of the Fleming Centre, a new research and public engagement facility to be built on the canal-side next to St Mary’s, just metres away from Fleming’s original discovery.

As Sir Alexander showed, innovation can come from the most unlikely of sources, we hope to carry on his legacy.