Is it time to update the Heimlich Manoeuvre? Dr Matt Pavitt recalls the experiences that led him to research this life-saving manoeuvre.

A little bit of history…

In 1974(1), Dr H Heimlich, published the results of an experimental animal study showing the effectiveness of the abdominal thrust manoeuvre to expel a foreign body from the upper airway. In a subsequent article in JAMA(2), Heimlich described his life-saving manoeuvre:

“Stand behind the victim and wrap your arms around the waist. Grasp your fist with your other hand and place the thumb side of your fist against the victim’s abdomen, slightly above the navel and below the rib cage. Press your fist into the victim’s abdomen with a quick upward thrust.”

Dr Heimlich died in December 2017. Four decades after his description of the abdominal thrust manoeuvre it was reported that aged 96 he used it to save the life of an 87-year-old woman choking in their elderly residence home.

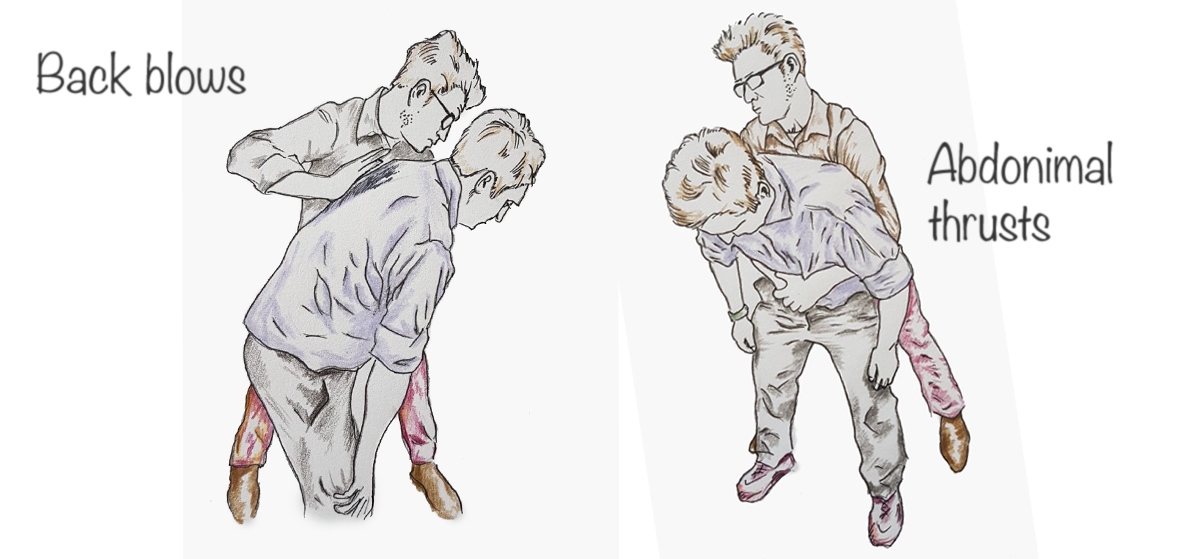

Current national guidance(3,4,5) on the treatment of complete foreign body airway obstruction (CFBAO) in conscious adults is a combination of back blows and abdominal thrusts with no preference on order.

Why study the abdominal thrust manoeuvre?

The National Safety Council, USA, reports that complete foreign body airway obstruction (CFBAO) is the fourth leading cause of ‘unintentional injury death’ with 5,051 reported deaths in 2015(6). The Office for National Statistics reports that there were 34 “unavoidable” deaths in the UK related to choking in 2015(7): this is likely to be an underestimate.

The seed to investigate the abdominal thrust manoeuvre came from Sir Macolm Green (Professor Emeritus, Imperial College London) and the personal experience of Dr Matt Hind (Consultant Respiratory Physician Royal Brompton Hospital.

Professor Green told me about the reasons he wanted to investigate this manoeuvre:

“It is not often that doctors save a young life in the community, in under ten minutes with no sequela. When I found myself doing just this on holiday in 1970 it had a big impact. Subsequent newspaper and other reports over the years confirmed my thoughts that the ‘Heimlich’ manoeuvre should be widely known and practised. As a respiratory physiologist with a research interest in the respiratory muscles I also believed that Heimlich’s original (and inspired) technique had some theoretical and practical defects which probably contributed to the reported complications. For many years I had it in mind to check my hypotheses, but for one reason and another, I did not get to study the physiology and pressures of abdominal thrusts until retirement gave me some spare time. The enthusiasm of colleagues in the respiratory muscle laboratory at the Royal Brompton brought the project to reality. The measurements confirmed my hypotheses and added some unexpected results.”

He went on to describe an event that lead him to perform the Heimlich himself:

“I was in a party of about 20 after a day skiing in Avoriaz. We were enjoying a meal of fondue bourguignonne with liberal local wine. The delicious beef segments (about trachea sized) were heated in oil at the table and consumed with chips and salad. The atmosphere was convivial. Suddenly I became aware of a member of the party further down the table standing up, gesticulating, clearly unable to speak and being hit on the back by his neighbour. The signs seemed pathognomonic of apnoea due to the completely obstructed airway (-they were choking). I rapidly went around the table to the subject, who by this time was looking decidedly grey, and performed two abdominal thrusts without success. By this time about three minutes must have passed so I decided I must act with maximum force, despite knowing the reported complications. To my relief a lump of meat shot out of the subject’s mouth, across the table. Both the subject and I took some deep breaths and dinner resumed for all.”

Professor Green isn’t alone in having first-hand experience of an event like this. Dr Hind described an even more personal incident to me:

“I was writing a research grant in a caravan in my garden while builders were renovating my house. I was alone, aside from my dog. Taking a second bite from a steak sandwich I became acutely aware of a bolus of steak stuck firmly in my gullet. I could not breathe in or out or make a sound. The meat was beyond the grasp of my fingers and there was no useful implement to hand. I realised the situation was precarious and ran to seek help from the builders. Rapidly a sense of impending doom developed. I performed the Heimlich manoeuvre on myself. The first attempt was unsuccessful, the second time I applied all my strength, the lump of steak dislodged and flew through the air. My dog jumped up and ate the meat before it hit the ground.”

So, to the research…

From a physiologist’s viewpoint the abdominal contents act in the same way as would a fluid-filled cavity. Thus, external pressure should increase the intra-abdominal pressure uniformly, regardless of where it is applied. To confirm this, we set out to investigate the physiology and measure the pressures generated by the abdominal thrust performed by an operator with his hands around the abdomen. We measured the pressures in the thorax and abdominal cavity of normal subjects by standard balloon catheters passed into the oesophagus and stomach respectively.

In a separate study, we also set out to understand the incidence of choking in London by analysing calls to the London Ambulance Service (LAS), given the paucity of data on the epidemiology of choking

Our findings:

Abdominal thrusts do increase abdominal and thoracic pressure significantly. They may not be effective in every case of CFBAO but our results are consistent with the numerous reports and anecdotes which confirm that they can save lives. Brain death from CFBAO occurs in 10 to 15 minutes so there is no time to recruit help or call emergency services.

Our studies found that the peak oesophageal pressures were not significantly different between the traditional abdominal thrust described by Heimlich (inwards and upwards) and circumferential ‘horizontal’ abdominal thrust (inwards only). This supports our hypothesis that performing the thrust inwards but not upwards over the fleshy part of the abdomen is effective.

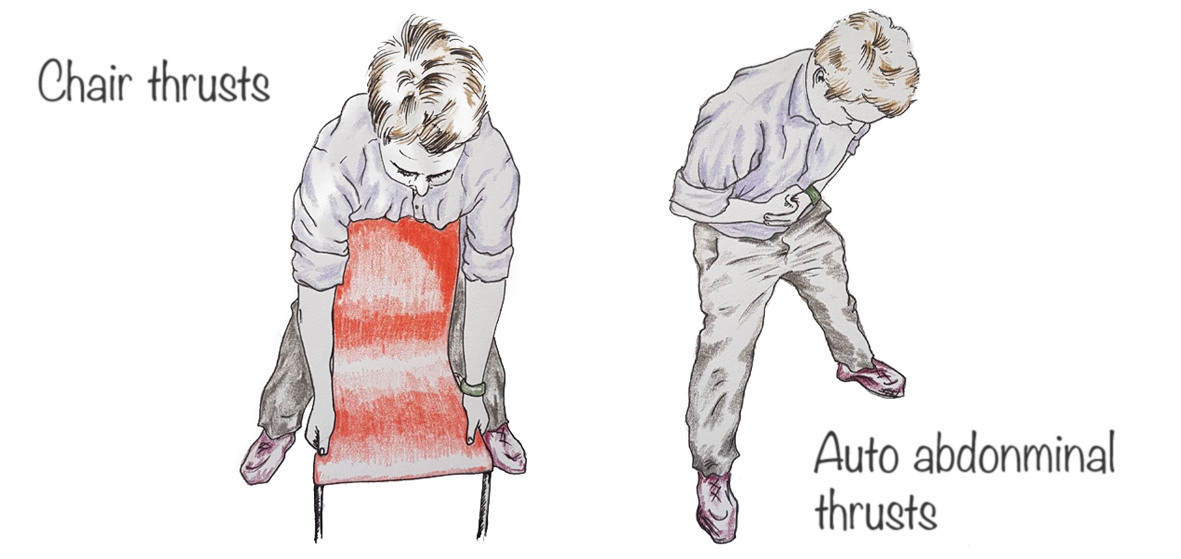

We investigated self-administering abdominal thrusts and found that they were also effective in generating positive intra-thoracic pressures. We also tried using the back of a chair to achieve the thrusts. Using gravity, bodyweight and arms the subject pulls the back of the chair to thrust it up into the abdomen. The pressures generated by this means were, significantly greater than by the other manoeuvers.

The full study can be found by in the Thorax Journal

Our conclusions:

This physiological data confirms that there is no need to pull upwards when doing abdominal thrusts. We conclude that the best technique is to pull sharply inwards over the fleshy part of the abdomen, at the level of the umbilicus, midway between the rib cage and the pelvis. This is just as effective as pulling upwards and is likely to reduce the risks of rib fractures, damage to the liver or spleen, or other complications.

It was to our surprise that self-administered abdominal thrusts could be as effective as those performed by others. However, it is possible that our subjects tended to contract their abdominal walls when anticipating a thrust, (which might not be the case in a real-life emergency) thus reducing the measured pressures for the external thrusts. We were interested to find that performing the chair thrusts could be very effective. This is important information as a chair is very often available when someone chokes, even if he/she is alone.

Another epidemiological study of ours found that choking is a substantial health problem with more than five calls per day by Londoners seeking emergency assistance. Choking is more frequent at the extremes of age and appears to have a higher incidence at lunch and dinnertime.

The full study can be found in BMJ Open Respiratory Respiratory

Professor Green added significant conclusions relating to women carrying children:

“It is conventionally suggested that abdominal thrusts should not be performed in pregnant women. This advice seems to me deeply flawed both in theory and as a result of our studies.

Firstly, it is hard to see why allowing a pregnant woman to die of CFBAO can be justified, even if there is a theoretical risk to her child.

Secondly, there is no evidence that coughing causes miscarriage even in the last trimester of pregnancy, and certainly not in the first six months. Pregnant women frequently cough, sometimes enough to break ribs, without harm to the foetus. Our studies found that abdominal thrusts cause abdominal pressure peaks of less than half those of spontaneous coughs performed by our subjects. So the risk to the foetus seems very small, and well worth taking if it saves a mother’s life (and thus potentially that of the foetus also).

It is my strong recommendation that the guidelines should be changed in this respect.”

Our recommendations…

The key to diagnosing complete airway obstruction is a conscious person, who is unable to breathe at all, nor to speak. Choking is a common problem. Self-administered thrusts appear to be as effective as first aider-administered ones, with a chair thrust appearing to be the most physiologically effective.

There should be greater public awareness of choking and its management with signs in restaurants being a possible way to reinforce this. We advise that everyone choking should, in the first instance, self-administer an abdominal thrust or perform a chair thrust. These manoeuvres should be more widely taught.

Dr Matt Pavitt (@DrMattPav) is a Clinical Research Fellow at the NHLI Respiratory Muscle Laboratory.

Illustrations by Dr Alice Myers.

References:

- HJ H. Pop goes the cafe coronary. Emergency Medicine 1974;6:154-55.

- Heimlich HJ, Hoffmann KA, Canestri FR. Food-choking and drowning deaths prevented by external subdiaphragmatic compression. Physiological basis. The Annals of thoracic surgery 1975;20(2):188-95. [published Online First: 1975/08/01]

- Sayre MR, Koster RW, Botha M, et al. Part 5: Adult basic life support: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation 2010;122(16 Suppl 2):S298-324. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.110.970996 [published Online First: 2010/10/22]

- Choices N. What should I do if someone is choking? – Health questions – NHS Choices. 2017

- Perkins GD, Handley AJ, Koster RW, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 2. Adult basic life support and automated external defibrillation. Resuscitation 2015;95:81-99. [published Online First: 2015/10/20]

- National Safety Council. Choking 2016.

- Statistics for National Statistics. Number of avoidable deaths by broad cause group, sex and 5-year age group, England and Wales 2017.