For World Hepatitis Day, Dr Ana Ortega-Prieto explains why she switched her research focus from hepatitis C to hepatitis B – a virus that continues its global spread despite an available vaccine.

When I first started to work on hepatitis C virus (HCV) for my PhD, the general conviction was that it was a dangerous pathogen with very unsuccessful treatments. In the past years, this has completely changed; patients used to endure one year of treatment with severe side effects, but can now expect just three months of treatment, which is generally well tolerated. The truly impressive part here is that treatment success went up from below 50% to well over 90%. This has triggered the World Health Organisation (WHO) to aim for the eradication of all viral hepatitis by 2030 – a very ambitious goal.

However, despite these truly life-transforming developments, people often forget that HCV has a big brother, which is not easily impressed by therapeutic interventions: hepatitis B virus (HBV). Very similar to HCV, HBV is a chronic viral infection affecting the liver, where it results in cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma – the most common type of primary liver cancer in adults.

Still a major health issue

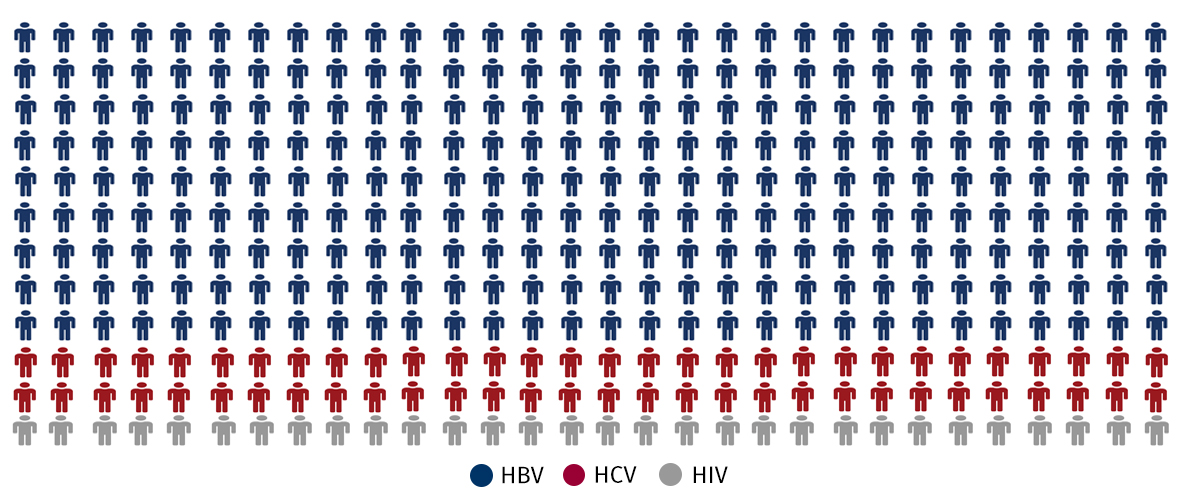

With over 257 million infected people, it dwarfs the 70 million people living with HCV infection and even the 35 million people living with HIV infection. Even though HBV can be effectively suppressed by therapy, this is by no means a cure and if treatment is stopped, HBV immediately comes back. Moreover, the virus is very often spread from mother to child and thus affects predominantly younger people. Despite an available vaccine, HBV continues its global spread.

What drew me to switching my field of research to HBV was, how little we knew about this virus until today. Unfortunately, it is among the most difficult viruses to work with in a laboratory. The fact that it only infects humans and chimpanzees means that testing new treatments using animal models is not possible and also growing the virus in the laboratory is very challenging. The receptor for HBV, which allows the virus to enter into human liver cells, was only identified a few years ago. This means that only now do we have some tools to our disposal to study, how the virus infects cells and ensures its persistence.

A stealth virus

Nevertheless, it is among the most fascinating viruses to work with, since its genome is extremely small, however, expertly adapted to evade immune responses. Infection with HBV itself does not result in many symptoms and it is only when the body’s immune system tries to eliminate the virus that the liver is caught in the crossfire and is damaged. The main problem in HBV infection is that, in contrast to HCV, HBV proteins do not lend themselves very well to the development of new antiviral drugs. The only protein with an enzymatic function has already been targeted with drugs but they uniformly do not cure patients.

So how do we reach the WHO goal of eradicating all viral hepatitis by 2030 if we are unable to effectively develop and test novel drugs? In my perspective, the answer to this is to motivate young scientists to take up the challenge and develop better tools, models and treatments in order to overcome the challenges ahead.

For many years, the dogma was that the availability of a vaccine for HBV limits the need for further research into curative therapies. However, the success story of HCV has ignited the minds of scientists working with HBV and what is now needed is an influx of young scientists to help make change happen and develop a cure for HBV infection.

Dr Ana Ortega-Prieto (@AnitaOP) is a postdoctoral research associate at Marcus Dorner’s Lab (@Dorner_Lab), Department of Medicine.

Read Professor Mark Thursz’s post on finding the missing millions infected with viral hepatitis on the IGHI Blog.

Following the launch of the Faculty of Medicine’s reorganised academic structure on 1 August 2019, this post was recategorised to Department of Infectious Disease.