As healthcare becomes high-tech with electronic healthcare records widely used, Eleanor Axson provides an insight into the power of medical record data for researchers.

When I was little, going to my GP meant seeing a manila file being pulled out from a mass of identical looking files and watching her write down my measurements and test results. The file grew as I did, each year adding to my entire medical history. All in one manila folder.

Things have changed. There is no longer a manila folder growing steadily right alongside me; rather, I watch my GP click and type all my medical history into a computer. Electronic healthcare records (EHR) have irreversibly changed our doctor-going experience and they are certainly here to stay. Your electronic healthcare record contains all the information your old paper one did. Demographics, vital statistics, diagnoses, medications, medical tests, etc.

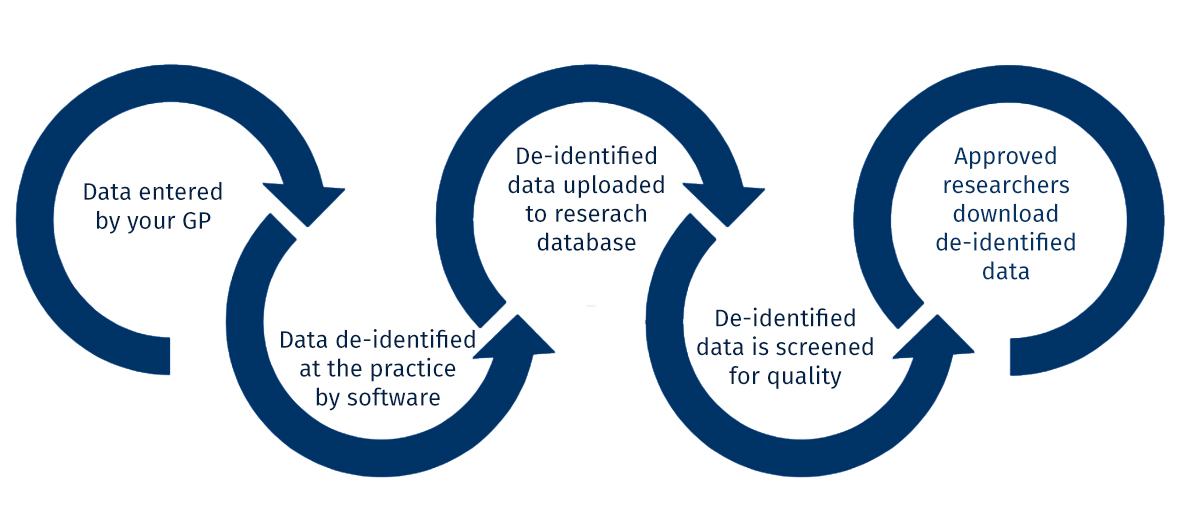

This data has far more potential than just letting your doctor know you had pneumonia in 2010. It can be safely de-identified, encrypted, and contribute to a research database for analysis by epidemiologists, like me.

The UK is a leader in EHR research

The UK is home to some of the largest de-identified primary care medical record research databases in the world. These databases, GOLD and Aurum, are from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) sponsored by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). GOLD and Aurum cover the lives of 35 million people, 10 million of whom are actively contributing data today. Additionally, this data can be linked to other electronic data sources, such as hospitalisation records, death certificates, and socioeconomic data.

Data from EHR is special, because it allows researchers to track healthcare patterns in real-life. We can also track disease patterns over time to answer questions such as, was this year’s influenza worse than last year’s, or is asthma on the rise? We can see how healthcare is actually being implemented, not just how we think it should be based on controlled studies. “We can’t just keep living in a world of controlled trials,” as my supervisor Dr Jennifer Quint notes. The real-world is not controlled, data from EHR allow us to see the big, messy picture.

Data from CPRD has been used in a variety of different studies, such as:

- Demonstrating there is no link between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism

- Examining characteristics of asthma patients and their risk for exacerbations

- Describing the risk for cardiovascular diseases in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Use of statins to lower risk of dementia

- Linking body mass index (BMI) and risk of cancer

Despite all the good that may come from you allowing your data to be used in research, the idea of a random person, like myself, being able to look at your medical record, may still be a bit daunting. How can you be sure that I don’t use your data against you?

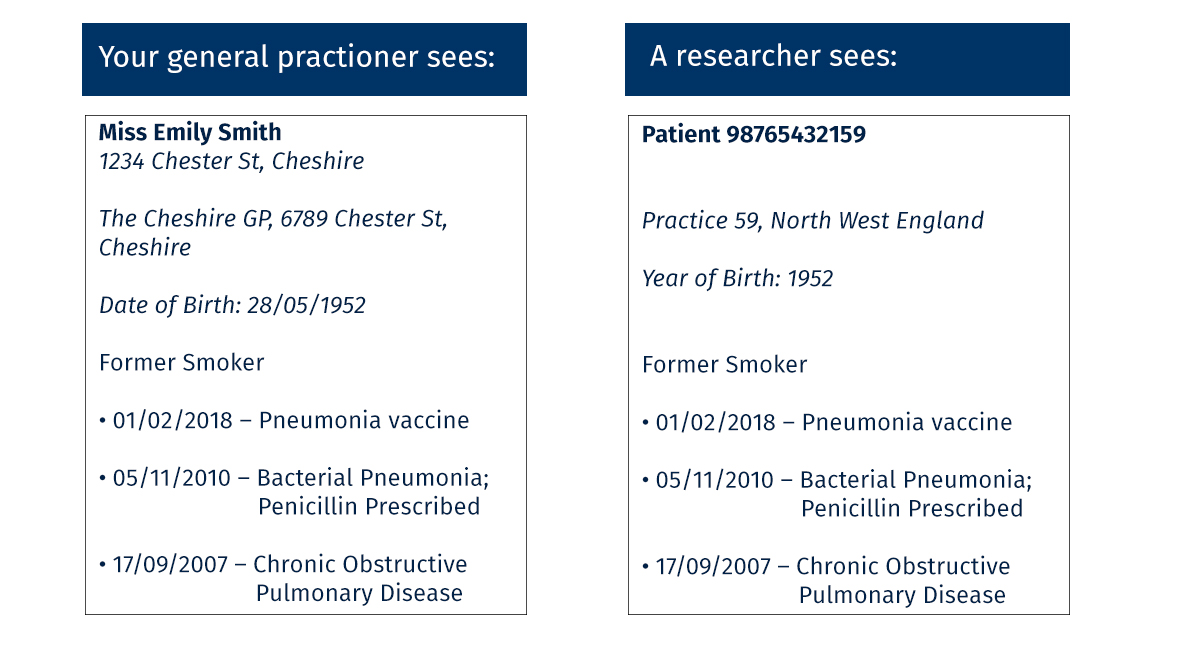

What your doctor sees vs. what I see

As a researcher, my study must be approved by an ethics committee, whose job it is to ensure that your data will be used to benefit medical research and public health. The committee also ensures that I have the proper experience and training in how to manage your data safely and securely. If the committee concludes that my study is worthwhile and that I am properly qualified, they will grant me access to only the data that I need, no more.

There are many steps taken to ensure your anonymity and the safety of your data. In the end, what I end up seeing as a researcher is different than what your GP sees:

This may not seem like such a huge difference, but the key lies in the fact that your data is de-identified before ever entering the research database.

This may not seem like such a huge difference, but the key lies in the fact that your data is de-identified before ever entering the research database.

How I use your data

My research relies completely on patients being willing for their data to be shared with researchers. I am investigating the interaction between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and heart failure (HF). COPD and HF share common risk factors, signs, and symptoms, making it difficult to diagnose one disease in the presence of the other and to describe their interaction. Using CPRD data, I am asking a number of questions to try and understand their relationship:

- How common is having both COPD and HF in the UK? Is this changing over time?

- Does having HF on top of COPD exacerbate COPD symptoms?

- Does type or severity of HF matter?

- Is COPD a risk factor for HF?

These questions cannot be answered by examining one medical record, but require hundreds-of-thousands. CPRD data is uniquely able to answer these questions because it allows me to see the records of hundreds-of-thousands of patients and track them over time. Your data is de-identified to protect your privacy, but also I don’t need to know who you are in order to answer my research questions. I don’t care about YOU. I care about all of you.

The decision is yours

Most importantly, you can opt-out of your data being used for research. It is always your decision whether or not you wish for your data to be included in any research schemes or databases. If you do chose to contribute, remember that researchers like me are not interested in you individually, no offense. Your data is pretty worthless on its own, as your personal medical record doesn’t answer the questions researchers are interested all by itself. We are much more interested in health patterns, which require information from lots of people. These are what allow us to identify public health priorities to present to government and health care agencies to implement policies that improve life in the UK and beyond.

Eleanor Axson (@EleaAx) is a research assistant in statistics and epidemiology and a PhD candidate in the Respiratory Epidemiology group (@RespEpi) at the National Heart and Lung Institute (NHLI).