Charlotte Roscoe highlights the problem of environmental inequality and explores how potential solutions such as urban green spaces may help to close the gap.

Whether it’s standing on picket lines with Mind the Pay Gap signs, whether it’s the rallying cry of Black Lives Matter, or surging child poverty across the UK: one thing inequality probably doesn’t mean to you, is city planning. Yet over 80% of the UK population live in urban areas, and the built environment is unequally impacting our health and wellbeing.

Not all urban neighbourhoods were built equal

Urban neighbourhoods designed in the past few decades of vehicle priority tend to be the most damaging to health. Car parks and roads have swallowed up our public spaces, and despite government strategies to reduce vehicle emissions via charging schemes, vehicles continue to dominate our streets.

Perhaps you’ve read headlines such as: “Traffic noise revealed as new urban killer”, or, “Each car in London costs NHS and society £8,000 due to air pollution”. These shocking news stories feature robust scientific evidence from the MRC Centre for Environment and Health, that both traffic noise and air pollution are linked to ill health, and even death.

Newsflash – traffic is bad for us!

Location, location, location

Daily doses of harmful traffic noise and air pollution vary depending on where we live. In UK cities, affluent areas are less polluted than more deprived areas. Even within the same neighbourhood, traffic noise and air pollution vary considerably. As a general rule of thumb, the more congested and the closer a road is to our home, the higher the concentration of pollution on our doorstep.

This means that people who live on busy and noisy high streets – who typically have lower incomes – carry the burden of both environmental and economic hardships, and pay the price with their health. Children, the elderly and those with chronic illnesses are most likely to be affected by pollution. Environmental inequality, like many other forms of inequality, is often invisible, and has been all too easy for politicians to ignore.

The current situation is stark, but there are solutions

Local councils can make a major difference by investing in multi-impact solutions. For example, Sheffield City Council’s Active Travel Commissioner – Dame Sarah Storey – is working with local communities to make streets more attractive and welcoming for cycling and walking, while also tackling traffic in residential areas. Her holistic approach is captured in the Sheffield Inspiration Story. The active travel solutions proposed not only benefit residents through a reduction in traffic-related pollution, they also encourage a more active lifestyle, with accompanying health benefits.

This month, the Mayor of London pledged, alongside 35 mayors from around the world, to reduce fine particulate matter (PM2.5) pollution across the capital to below the limit set by the World Health Organisation by 2030. Particulate matter is emitted from vehicle engines, tyre and brake wear, as well as from wood burning stoves. The recent introduction of the Ultra Low Emission Zone in London will reduce traffic-related air pollution. Added to this, PM2.5 air pollution targets will be enshrined in law as part of the Environment Bill. However, meeting targets in London is going to require major public infrastructure investment (and no, I’m not talking about electric vehicle charging points!)

Less urban traffic

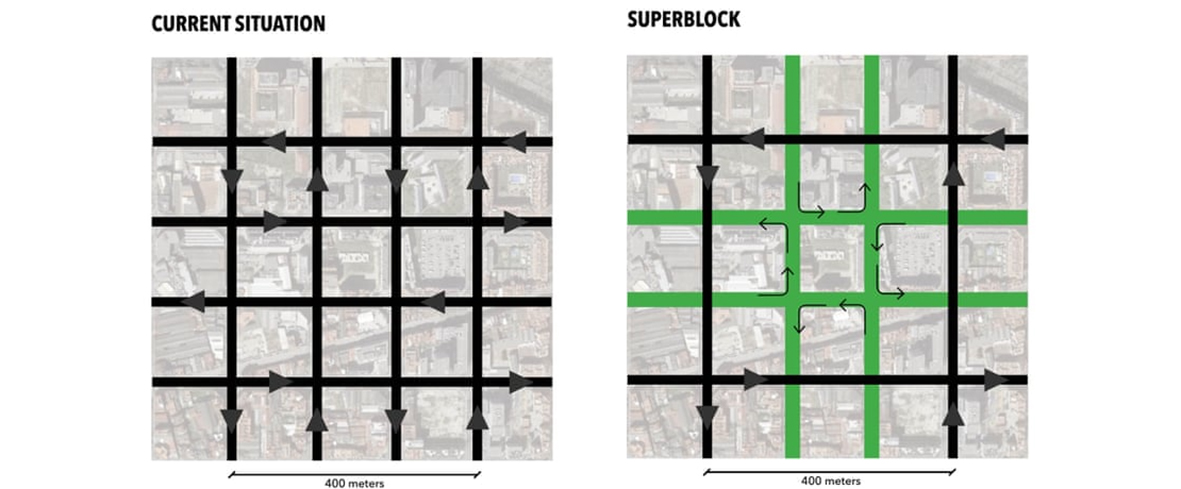

Over in Barcelona, the city council have made a bold move to free up public space and redefine urban mobility. The ‘superblock model’ redirects traffic circulation to the periphery of superblocks (9 of today’s blocks arranged 3 x 3). In turn, this frees up road space in the interior of each superblock. The ex-roads are transformed into public space for walking, cycling, playing, and breathing cleaner air. To complement the superblocks, the city council is introducing 300km of cycling lanes, and investing in public transport networks.

The superblock model is ambitious; by implementing changes simultaneously, the city aims to reduce car use by 21% over the next two years and increase mobility by foot, bike and public transport. Researchers have estimated that almost 700 premature deaths will be avoided annually from these changes. Health benefits will come from reductions in air pollution, noise and heat-stress, and from increases in active travel and green space.

More urban green spaces

Any land covered in vegetation – such as parks, woods, cemeteries, playing fields and street trees – is green space. Typically, you don’t find many cars zipping through parks. This may sound obvious, but fewer vehicles in greener areas means less pollution sources, and lower levels of pollution. Plus, large and open green spaces allow air pollutants to disperse rather than becoming trapped and reaching toxic concentrations between buildings. What’s more, vegetation can capture pollutants and help purify the air.

Living in greener environs is associated with lower likelihood of disease and reduced risk of early death, and might also be linked with a whole host of benefits throughout life. From healthier, heavier birth weight in newborns, to better cognitive development in school children, to slower cognitive decline in older adults. We know that to live a healthy life, there are many factors within our control, such as exercise and diet. However, living in greener and healthier neighbourhoods is often out of our hands.

Why we should care

If you ask me, what does inequality mean? I’d say it means poor quality environments for the urban vulnerable. Polluted neighbourhoods plagued by car-centric planning decisions, with a lack of green space compounding negative health effects. It is clear to me that to tackle environmental inequalities in cities, we don’t need a technological breakthrough. We need to redesign our neighbourhoods for people, instead of cars.

The new Environment Bill (15 October 2019) will give greater power to local governments to address environmental issues. If you want less polluted streets, more green space and better public transport infrastructure, you can ask your local council or your local MP to provide a healthier, greener neighbourhood.

Why I care

My PhD research at the MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health looks at the link between traffic pollution, green spaces and health in older adults. My work explores how urban green spaces in local neighbourhoods might help older adults maintain a healthy heart and circulatory system. To do this, I estimate the impact of trees and green spaces in reducing air pollution, and assess if vegetation surrounding roads and paths near to home encourages walking in older adults.

I work with the UK Biobank database, which has collected medical and lifestyle information from 500,000 volunteers. Using a geographic information system (GIS), I assess the amount of vegetation around each participant’s home, and its impact on health. I also model other built environment pollutants, such as air pollution and traffic noise levels, to help disentangle protective and harmful built environment features.

Public engagement is important; that’s why I’ve written this post, as well as collaborated this year with artists on an installation, GREEN SPACE. It is the public who have the power to drive environmental policy change.

Charlotte Roscoe (@CharlieJRoscoe) is a PhD Candidate in Environmental Epidemiology at the MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health at Imperial’s School of Public Health.

Image credit: GREEN SPACE artwork by Enya Lachman-Curl, photographed by Jack Kenyon.

One comment for “What is environmental inequality and why should we care?”

Comments are closed.