Dr Alejandra Tomas, Senior Lecturer at the Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction, explores new and emerging incretin-based therapies for managing diabetes.

Diabetes is a disease that has reached epidemic proportions, with millions of people dying or suffering from a myriad of associated complications. Given that cases are projected to increase worldwide over the coming decades – especially in low- and middle-income countries – there is an urgent need to develop and deploy effective treatments for the disease.

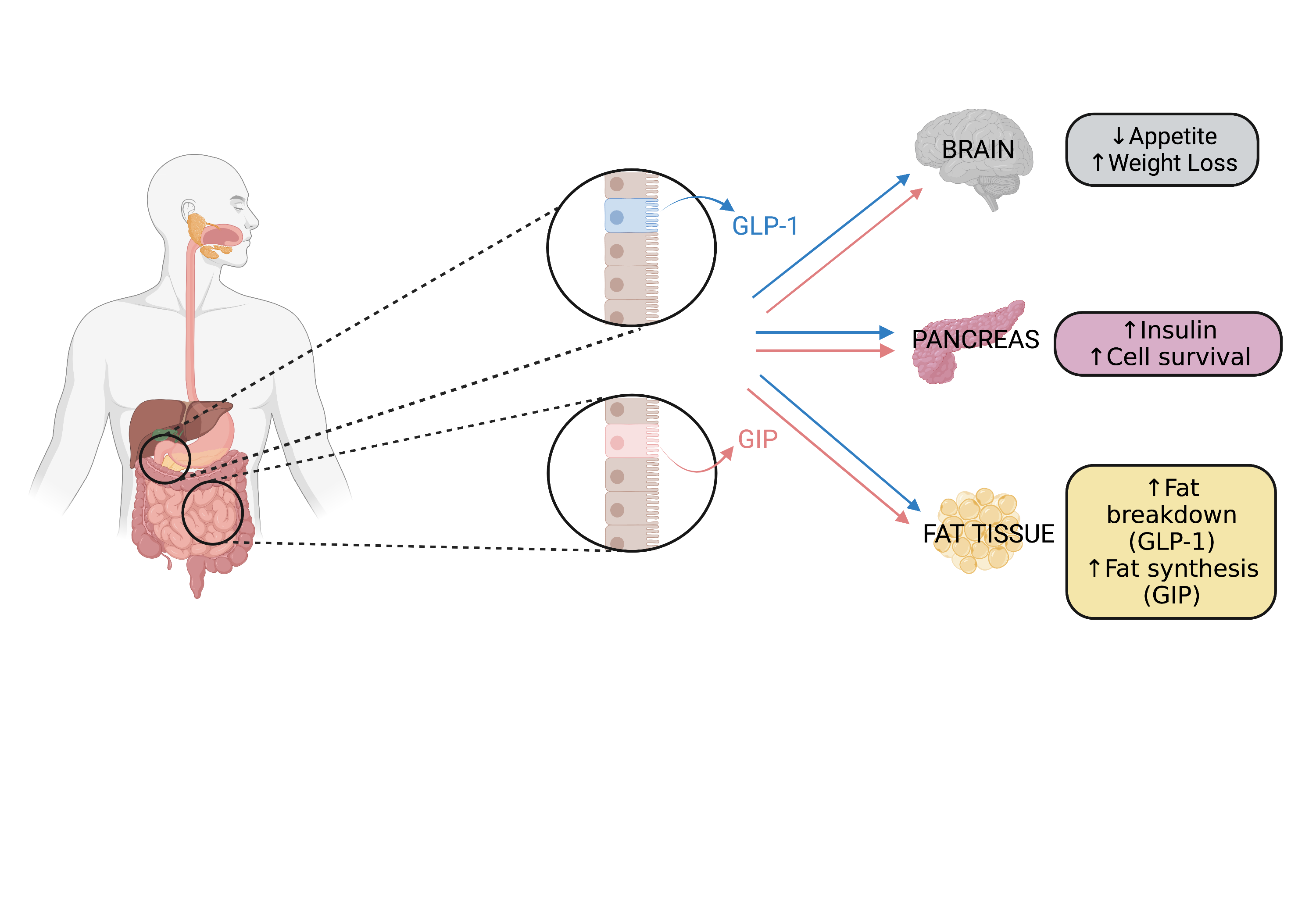

Amongst the current treatments for diabetes are incretin therapies which are based on hormones called ‘incretins’, released from the gut after we eat. These gut hormones stimulate the pancreas to produce extra insulin (responsible for regulating blood sugar) by binding to proteins at its surface called ‘receptors’. Incretins also activate receptors in the brain that promote feelings of fullness and reduce appetite – an added benefit for individuals who need to lose weight.

The two incretin hormones

There are two types of incretins, GLP-1 and GIP, and each one binds to its own receptor. So far, most incretin therapies have been directed at the GLP-1 receptor because the GIP receptor does not work well in people with diabetes. However, we now know that when blood sugar levels get under control, the GIP receptor starts to work more effectively again, and as this is a very strong receptor, there is a good case for developing therapies that target the GLP-1 receptor and the GIP receptor simultaneously. This has just been achieved in a new therapy called “tirzepatide”, recently approved in the UK. Tirzepatide has shown superior effects in controlling blood sugar levels as well as in promoting weight loss in clinical trials.

Understanding how both incretin receptors work together

The way that incretin receptors work together in the pancreas is not yet very clear. While they both promote insulin release, the GLP-1 receptor reduces the release of another hormone made by the pancreas called ‘glucagon’, which balances the effects of insulin on blood sugar, while the GIP receptor promotes glucagon release. In the past, it was thought that glucagon release was bad for diabetes as it causes blood sugar levels to spike because of its effects in the liver. However, we now know that glucagon is necessary to enable the pancreas to release optimal levels of insulin. It is therefore unclear whether it is better for glucagon to go up or down. It is also uncertain how important each receptor is to control insulin and glucagon levels.

Optimising GLP-1/GIP targeting for individual patients

We are currently working to clarify how exactly each receptor works by investigating how they move across the cells of the pancreas, the signals they send, and the partners they interact with. We are also analysing the genetic variants of each receptor that exist in the population to see how these changes in people’s genes can affect how each receptor works for them.

We hope that this work will help us understand why these receptors work differently to each other, why they have different strengths at triggering the release of insulin and glucagon, and how changes in the genes that code for them modify the way they work in specific people.