Dr David Salman from the School of Public Health discusses how digital interventions could help people return to fitness following a period of illness.

I am a GP, researcher, and work at the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust sport and exercise medicine clinic. Part of my work is to help people become more physically active – important because it is one of the few interventions that can improve health in many different ways. If we had a similar drug or intervention that reduced the risk of heart disease, diabetes, dementia, depression, risk of falls, and several cancers, then everyone would probably be on it. The problem is that almost one-third of people in the UK are not physically active enough for good health. This is partly because barriers to being physically active exist across individual and cultural factors, such as illness, pain or different conceptions of what physical activity or exercise mean; infrastructure aspects such as safety, facilities and lighting, through to national and global policy. Therefore, this wonder medicine is not equally available to all.

Remote guidance

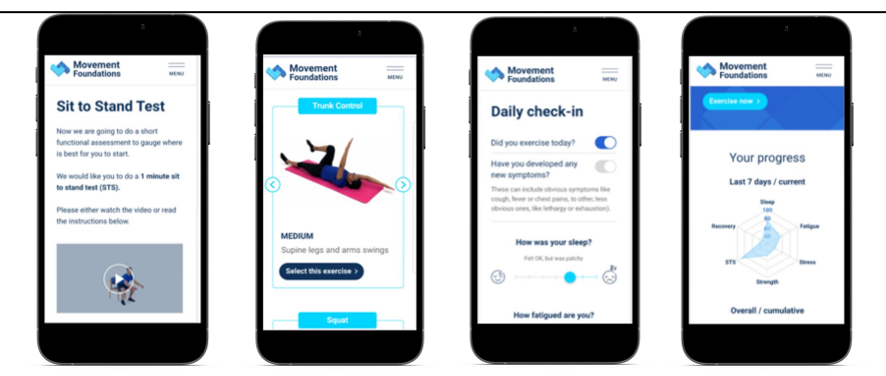

One challenge for some people is to return to physical activity following a period of illness or inactivity, where you can get much more tired more quickly, and things might be sore, or you might feel discomfort. Some people will have lost strength, so might be feeling less confident in some movements. We at Imperial MSk Lab have established a partnership with colleagues in military exercise rehabilitation, in physiotherapy, and in the commercial rehabilitation platform Rehab Guru, to develop a piece of software that could guide people to resume physical activity following illness or inactivity. It involved an initial gentle test of ‘fitness’, following which people are entered into a starting level appropriate for them. It then guides people through exercises aimed at replicating the complex movements required of everyday life (such as pushing or pulling something, hinging at the waist, rotating etc). Each day, users were asked to respond to questions on broader measures of their health and wellbeing, such as their sleep, muscle soreness, stress, fatigue and recovery levels. These, together with their progress through the programme, allowed the software to guide that person to progress to a higher level, stay at the same level, or take a period of active recovery.

Three key themes

We wanted to know how much of an impact the software had on people, and so tested it using a method where people are interviewed, and their perspectives are analysed to generate ‘themes’. One issue was that, out of the 22 people who expressed interest in the study, only nine completed the study. This tells us that this tool did little to overcome the basic barriers to being physically active, and that the people that used it were potentially more motivated to do so anyway. We found three key themes in what people told us. First, that the software helped people develop movement skills, which increased their capacity for moving more. Second, that it helped people find opportunities, and overcome some barriers, to be physically active. It also motivated them, primarily by helping them reflect on the effect that being physically active had on them. Finally, the fact that the software helped people progress in a gentle and graduated way, and was structured, was viewed positively, and people did not feel pushed. They also felt they could adapt it to suit them. In short, people felt protected, and could take things at a pace suitable for them. This told us a lot about physical activity and movement.

Self-reflection

We previously believed that movement skills were a bit like cooking: provide people with some instruction, and they will then incorporate it into their daily lives. However, this doesn’t seem to be the case. These results show us that people will be motivated to do something when they feel the effect it has on them, and then it starts to become a habit. Although people who are recovering from illness or returning to physical activity following a period of being inactive do appreciate having some instruction within a carefully guided programme, self-reflection is important to help people feel that what they are doing is positive, and that they should do more.

So, in short, our message is: do something, even if it is only a little. Even if it is just getting off the bus a stop early or walking home with the shopping instead of driving. And be proud of that. See how it makes you feel; keep doing it and do more if you can.

Dr David Salman is a post-doctoral research fellow at the School of Public Health, currently working in the MSk lab.

Read the full publication: Salman et al., Movement Foundations. The perceived impact of a digital rehabilitation tool for returning to fitness following a period of illness, including COVID-19 infection: a qualitative study. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine.