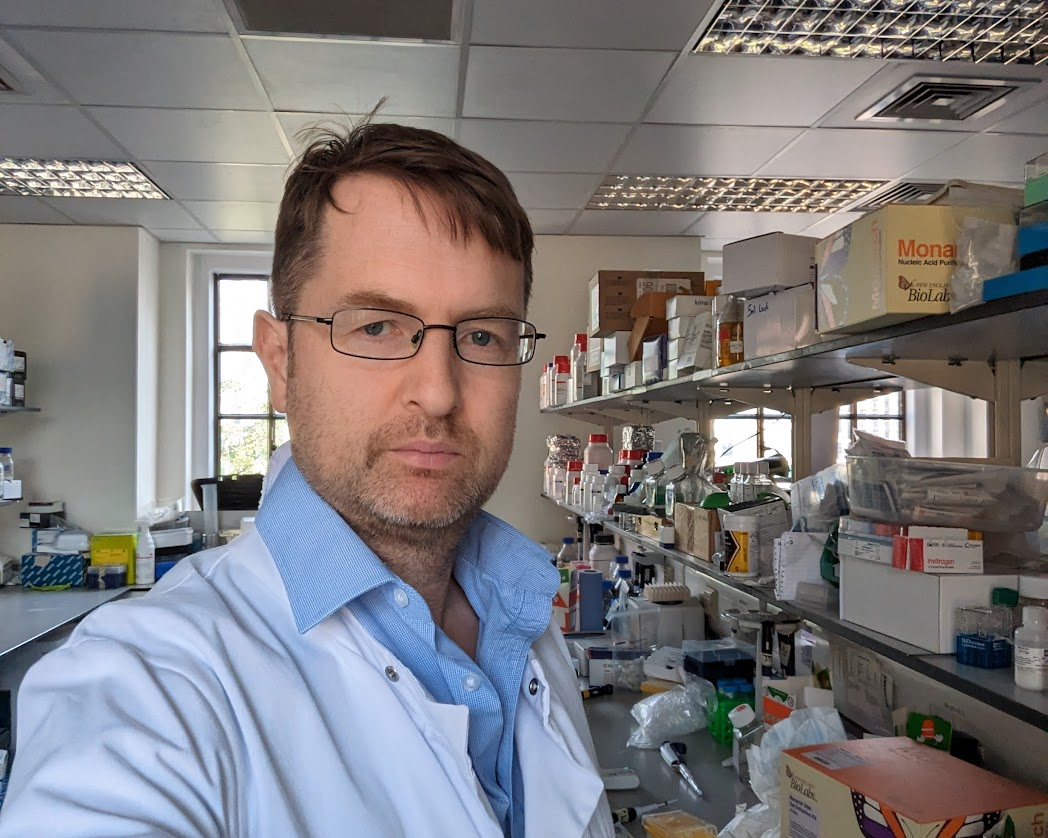

On World Hepatitis Day, Clinical Associate Professor, Dr Shevanthi Nayagam, working across the School of Public Health and Department of Metabolism, Digestion, and Reproduction, shares how her research is helping shape global and national strategies to eliminate hepatitis B (HBV). From modelling vaccine impact to supporting birth dose policies in Africa, she highlights the power of evidence, collaboration, and local action in tackling this silent epidemic.

Hepatitis B is a virus that attacks the liver and, over time, can cause serious complications such as cirrhosis and liver cancer. What makes it particularly dangerous is that many people don’t realise that they are infected – it can silently damage the liver for years without causing symptoms.

One of the things that motivated me to start research in hepatitis B over a decade ago, was just how little attention this virus received, despite affecting 254 million people. In 2022 it was estimated to have caused 1.1 million deaths. I’ve seen how hepatitis B continues to affect the lives of those living with the infection and their families – particularly in low- and middle-income countries where prevention, diagnosis and treatment are often out of reach.

My translational research sits at the intersection of clinical epidemiology, modelling, and health economics – all aimed at an overarching goal: supporting countries to eliminate viral hepatitis through evidence-based decision making.

A big part of my work involves connecting the global with the local. This dual approach helps ensure that international recommendations are grounded in real-world data . Of course, this kind of work isn’t done in isolation. Everything we do depends on strong collaboration with a wide range of partners – including clinicians, scientists, ministries of health, policy makers and funding agencies.

Virus Appreciation Day, celebrated annually on 3 October, serves a dual purpose: to foster respect and understanding for viruses while raising awareness about their serious impacts on health. To mark the day,

Virus Appreciation Day, celebrated annually on 3 October, serves a dual purpose: to foster respect and understanding for viruses while raising awareness about their serious impacts on health. To mark the day,