Ahead of the 2018 FIFA World Cup kick off, Dr Peter Wright explores how the stress and excitement of watching football isn’t all fun and games for our cardiovascular health.

Since time immemorial, sport has functioned as a useful substitute for direct physical conflict between, tribes, towns and nations. This year all eyes turn towards Russia, where the 21st edition of the FIFA World Cup will take place. The Russian word ‘mira’ may translate as both ‘world’ and ‘peace’, but as the pre-eminent competition of humanity’s favourite sport, ‘Чемпионат мира по футболу 2018’ is likely to be anything but relaxing for the players, officials and millions of spectators worldwide.

It’s a slightly odd concept that the last grouping would derive anything other than enjoyment from watching some of the globe’s finest sportsmen pitted against each other. But, perhaps the role of sport in civilization gives the act of watching the beautiful game a much darker aspect. As humans, whether we are sport fans or not, we all reflexively understand that people experience deep emotions even if they are just in attendance at these events. The language within which the media wraps the spectacle is illustrative, and of course contributes to the ‘feverish’ or ‘heart-stopping’ feelings felt by the audience.

But what if anything is known to science about the effects of these events on the cardiovascular health of the audience? Where does the line between figurative and actual physical stress blur and what, if any, dangers are there?

A dangerous game, win or lose

As an Englishman, nothing is more terrifying to me than the thought of a penalty shoot-out. All those hours of football played over the four-year qualification period, all those years of perceived underachievement, laid on the shoulders of players who may achieve glory or infamy with a single kick.

On the 30 June 1998, the day England were knocked out of the World Cup by Argentina following such a shoot-out, admissions for acute myocardial infarction (MI) – commonly called a ‘heart attack’ – increased by 25%(1). Intriguingly, on the other side of the channel in the same year, on 12 July, when France hosted and won the World Cup Final, the death rate from MI was reduced by about 33%(2). So-called all-cause mortality (the total number of deaths in the population) was no different.

A prospective study was conducted in Germany in 2006 during the tournament, and discovered that on days when the German national team were playing the rate of cardiac emergencies was increased 2.66 times(3). So it would appear that even almost complete assurance of victory is no protection against the harmful effects of watching football!

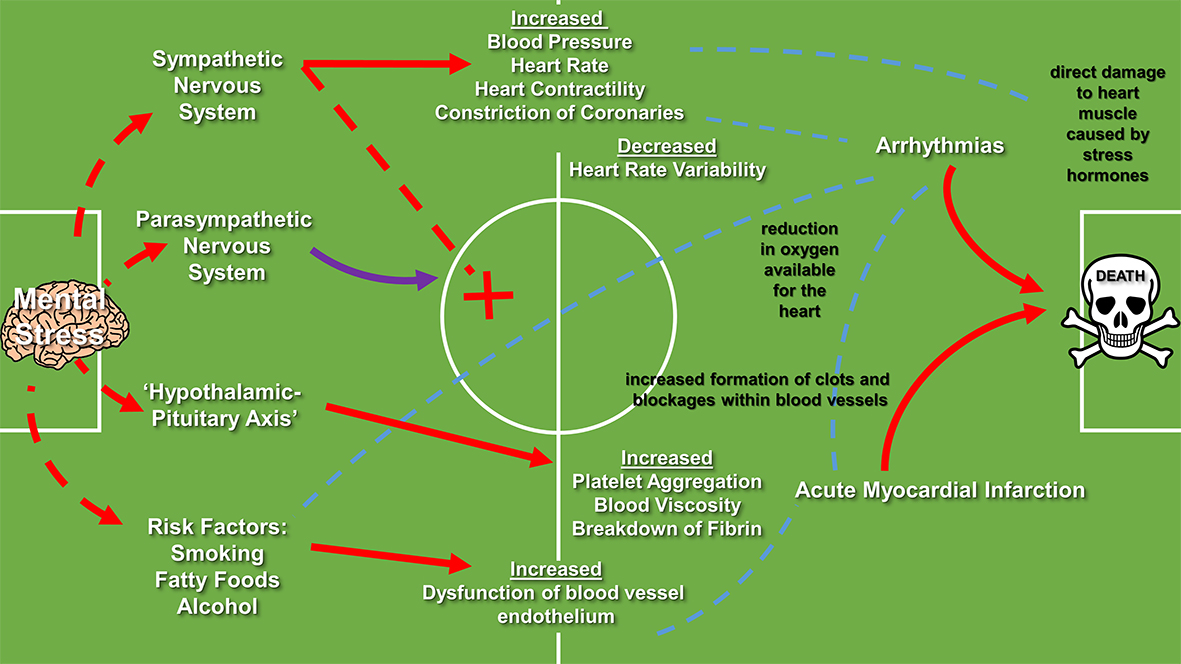

What could it be about these games which may actually be killing people? In an expansive piece by Leeka et al.(4) which looked at cardiovascular events during all sporting events, the processes underlying the damage (or the pathophysiology) are explained as the interaction of intrinsic physiological mechanisms within people due to stress and their effects on behaviour.

Clearly, the spectator is initially placed under mental stress due to the importance of the game, owing to factors such as human competitiveness as well as the interaction of sport with national and personal identity. These psychological factors nonetheless give rise to physical effects such as increased neural activity, coordinated by a number of networks such as the sympathetic nervous system. This is perhaps one of the best-known components of the human stress response as it controls the ‘fight or flight’ reflex. Those butterflies you feel just before kick-off are part of a primordial system that allows you to anticipate and respond to threats.

Fight or flight takes its toll over time

During this response neurotransmitters such as adrenaline and similar molecules are released and increase the output of your cardiovascular system. Like many adaptations of physiology, this has an evolutionarily useful acute effect, whereby your caveman ancestors would have been perfectly prepared to run from a lion or fight-off competitors. However, these periods may not have usually lasted more than a few minutes. We are not, perhaps, evolved to panic about Joe Hart fumbling crosses for 90 minutes.

Increased cardiac activity due to adrenaline can have the effect of physically disturbing plaques (fatty deposits) within your blood vessels. These blockages in the arteries of your heart can lead to parts of the muscle being suffocated, which is the basis of myocardial infarction. High-adrenergic states may also disturb the electrical activity of your heart causing the contraction to lose its synchrony and cease the normal pumping of blood, ultimately leading to death. Finally, molecules such as adrenaline may actively damage the heart muscle cells – known as cardiomyocytes.

Researchers such as myself have shown in animal models that large quantities of adrenaline (or a synthetic analogue known as isoprenaline) might precipitate a form of acute heart failure known as Takotsubo, or broken heart syndrome. Initially this disorder appears similar to MI, but has a different course and causative factors. We speculate that the organisation of the heart is well evolved to deal well with acute but not chronic stress. It has also had very little time to evolve to compensate for the behaviour modern sports fans may indulge in to dampen the stress of the event. Smoking, alcohol and fatty foods are all cardiovascular risk factors, and abusing them may contribute to the enhanced risk of cardiovascular events during football matches.

So if you’d like to avoid becoming a statistic during the World Cup finals this year, it would seem sensible to take it easy – go steady on the alcohol and fatty food (why are you still smoking?). Also, maybe we could try to be philosophical. How can you change the outcome of a game played on the other side of the world by getting stressed?

After all, it’s only a game, not life or death.

Right?

Peter Wright is a Post-Doctoral researcher jointly within the Functional Microscopy and Cellular Electrophysiology groups at the National Heart and Lung Institute. His work is funded by the MRC and BHF.

References:

- Admissions for myocardial infarction and World Cup football: database survey

- Berthier F, Boulay F. Lower myocardial infarction mortality in French men the day France won the 1998 World Cup of football. Heart. 2003;89(5):555-556.

- Wilbert-Lampen U et al. Cardiovascular Events during World Cup Soccer. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:475-483

- Leeka J, Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. Sporting Events Affect Spectators’ Cardiovascular Mortality: It Is Not Just a Game. Am. J. Med. 2010;123(11):972-77.

Regarding your comment “After all its only a game, not life and death, right?”

Legendary football manager Bill Shankly would not agree. He one famously commented that it is far more important than that! However, in fairness to your other points Bill did unfortunately suffer from heart trouble.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xodsnEQC-H0

https://www.theguardian.com/football/2017/sep/29/bill-shankly-liverpool-football-manager-dies-1981