Dr Kirk Taylor looks back at over 30 years of the HIV epidemic, from the advent of preventative therapy to the impact of HIV stigma that continues to plague forgotten populations.

Thirty years on from the first World AIDS Day we have seen enormous global progress towards ending the epidemic. The change that has happened within my lifetime is astonishing; HIV has gone from being a death sentence to a manageable condition with strategies to prevent transmission altogether. This World AIDS Day, I highlight the milestones achieved and where there is still work to do.

Testing, testing, testing

The number of people living with HIV has been steadily rising (37 million in 2017), whilst the level of new HIV infections has been decreasing. Current estimates suggest that only 75% of people living with HIV know their status. UNAIDS launched an ambitious target in 2017, so that 90% of all people living with HIV would know their status. There are several ways to test for HIV and some kits can be bought over the counter for use at home. This has been a huge step forward, but the cost (£30/kit) remains prohibitive for many. Most HIV tests can only detect antibodies raised against the virus which takes time. The most accurate results are obtained three months after potential exposure to the virus. More sensitive options to detect the virus after one month are also available. Given the delay between exposure to HIV and a positive test result, it is important for at-risk individuals to be tested regularly. People who think they have been exposed to HIV may be offered immediate therapy, within 72 hours, to prevent infection (post-exposure prophylaxis is described below).

Testing is routinely performed in sexual health clinics in the UK and in HIV clinics or hospitals in African countries (although more limited). UNAIDS reported that only 45% of people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa know their HIV status. Clearly, there is more work to be done to bring testing to these communities.

What treatments are available?

When the HIV epidemic began there were no treatments. Patients would progress to AIDS and be offered palliative care only. It took six years for the first treatment – AZT (Zidovudine) – to be licenced. Drug discovery gradually increased pace with 12 drugs licenced in a decade. A major challenge in the treatment of HIV is that the virus rapidly changes, or mutates, to outwit the drugs and become resistant. The advent of combination therapy in 1996 was a game changer that has been linked to cutting death rates by almost half.

Speaking to Dr Marta Boffito (Clinical lead for HIV treatment and prevention at Chelsea Westminster Hospital) she reflected on the impact of combination therapy saying that the greatest change during her career was “the introduction of combination therapy and seeing how her patients stopped dying from AIDS and either lived or even recovered.” Moving forward, Dr Boffito commented on how we can tackle stigma by integrating services, such as geriatric and cardiology care for an ageing population living with HIV.

Advances in the treatment and management of HIV continue and, with the introduction of new generation drugs, there is the possibility of reducing the drug burden with dual therapy (Gemini study). The future of HIV therapy is exciting with increased patient choice, the potential for personalised therapies, long-acting injectables and ongoing work into HIV vaccines and cure.

Being PrEP-pared can prevent HIV

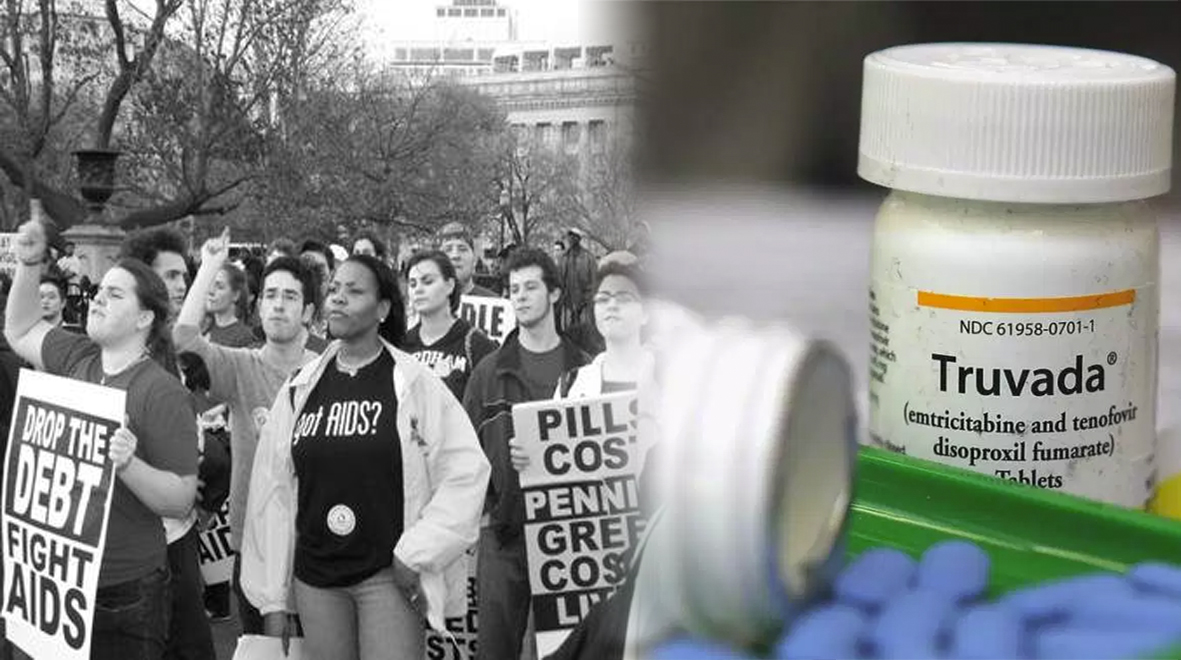

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) have been, arguably, the greatest breakthroughs in HIV prevention. PrEP consists of two HIV drugs that you take for up to 7 days before sex, to prevent HIV transmission, and PEP is three HIV drugs, taken for one-month following potential exposure to HIV. Several clinical trials have shown PrEP to be an effective strategy for HIV prevention. Interviews conducted alongside clinical trials report that the mental health and outlook on life for PrEP-users is improved compared to non-PrEP users.

Access to PrEP in the UK is limited and varies depending on where you live. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland offer PrEP on the NHS through different schemes. Meanwhile, NHS England is in the process of running a three-year feasibility study that will enrol 13,000 people ‘at-risk’ individuals. It is hoped that this will lay the groundwork for PrEP roll-out across the UK. Several people in parliament have called for PrEP to be rolled-out immediately, based on available evidence showing its effectiveness.

It appears the political debate in England has shifted to one purely about the cost of PrEP provision and it fails to consider the benefits of reduced HIV burden on healthcare providers, savings from lifetime antiretroviral therapy prescriptions and, most importantly, the value of reducing stigma and serophobia in improving mental health for at-risk individuals.

A recent study demonstrates that in couples where one partner is living with HIV and the other is not, that if their viral load is undetectable, the virus is untransmissiable. When presented in Amsterdam 2018 the lead scientist predicted that you would need to have condomless sex for 419 years before you contracted HIV. One warning that has followed is that although HIV transmission can be prevented, the risk from other sexually transmitted infections and/or pregnancy continues, therefore appropriate precautions should be taken (e.g. condom use and regular STI screening).

Forgotten populations and the impact of stigma

So, we know that people living with HIV that stick to their drugs and achieve an undetectable level of virus can’t pass it on (this is also known as U=U). This means that by increasing HIV testing (so people know their status), getting people onto effective therapy and reducing the level of their virus, we can eventually end HIV transmission. However, social and political attitudes since the 1980s have led to a culture of stigma around HIV and reduced adherence to HIV therapy. It was thanks to the efforts of activist groups, such as Act-Up, fighting for equality of access to treatment and recognising communities of people living with HIV, that stigma could begin to be challenged. Closer to home, itwas the actions of people like Princess Diana shaking hands with an AIDS patient that started to break down the stigma. There is clearly more work to be done but there is evidence to suggest that improved mental health status is linked with increased adherence to HIV therapy.

Women living with HIV also face unique problems as they are vastly underrepresented in clinical trials and gender-related issues are often discovered at a late stage. Dr Boffito suggests that we need to dedicate more studies to women coupled with community engagement to understand their bespoke needs.

There is more work to be done as stigma continues to plague forgotten populations, such as sex workers, transgender women, victims of gender-based violence, children living with HIV from birth and gay men living in countries where homosexuality is criminalised. Only by reaching these communities, increasing access to testing and HIV drugs can we hope to bring an end to the HIV epidemic.

Living healthily with HIV

Despite more than 100,000 people living with HIV in the UK, only 442 people died from AIDS-related conditions in 2016. Late diagnosis and non-adherence to HIV drugs are leading factors in the development of AIDS. Indeed, life expectancy for people diagnosed with HIV, that stick to their treatments, is now close to that of HIV negative individuals. There is growing evidence that people living with HIV have a greater chance of heart disease and that certain HIV drugs may increase this risk further. This increased chance may be due to a change in how the cells responsible for blood clotting (platelets) behave. I recently presented work from the Platelet Biology Group on how these cells respond to HIV drugs at meetings in Amsterdam and Boston. We continue to work on the mechanics and have extended our studies to look at the role of the blood vessel too. We hope that our research can improve the quality of life for people living with HIV. Given that HIV-negative populations are now taking HIV drugs routinely, as PrEP, we are keen to understand if the drugs have an impact in this population.

On the 30th Anniversary of world AIDS Day, we should celebrate the progress that has been achieved – AIDS-related deaths are declining globally, more people are diagnosed early and have near-normal life expectancies, stigma around HIV is on the decline and better, longer acting drugs and vaccines are being developed. It is important to remember that without the campaigning and advocacy of the community, such rapid progress would not have been possible. The next challenge is to maintain the momentum and ensure that we can deliver these outcomes for Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe and Central Asia too!

Dr Kirk Taylor (@Dr_KTaylor) is a post-doctoral researcher at the National Heart and Lung Institute and is investigating the impact of anti-retroviral therapies on platelet function.