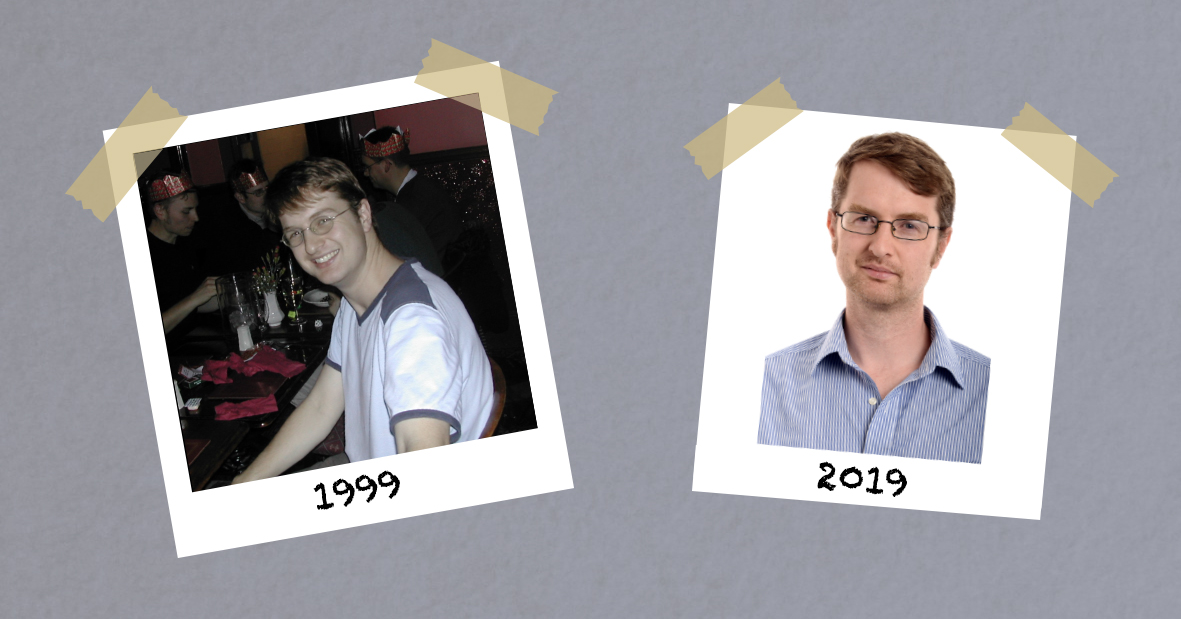

Marking 20 years since Dr John Tregoning arrived at Imperial College London as a PhD student, he reflects on what he’s learnt over his career to date.

On 1 October 1999, I walked out of South Kensington tube station, fresh-faced and ready to start my PhD. 20 years later as I walk out of the same tube station to the same campus of the same university (still fresh-faced I like to think), the question is, have I learnt anything?

Spoiler alert – the answer is yes, but a guarded yes, from a staggeringly low starting point, like Marianas Trench low. Some of what I have learned is fairly niche and only useful if you work in a biomedical lab – like how to open a tightly screwed plastic tube with one hand whilst avoiding infecting yourself with influenza, some are a bit more generally applicable to having a career in science, especially if you are or want to run your own research group, and some grandiosely I think might be applicable to everyone.

School’s out

Working in a university, this may be a bit unnecessary to point out, but education never ends: we are continually learning and evolving. Even if you were able to recall all the facts from school into adulthood it is likely that they are now either outdated or completely irrelevant to the work you do. We need to retrain: to become parents, to become managers, to change roles, to retire gracefully. And for these new roles, there is no pass/fail test to say how well you have done, it is all a bit woolly. So we need effective strategies to learn for life: both for ourselves and for the others – students, children, co-workers – that we might need to train.

The skills to pay the bills

The skills you need for your PhD are not enough for the rest of your career. Being good in the lab or field or computer terminal is important, but at some point, you need more. You need social intelligence too (sometimes called soft skills): being able to work with other people. A lot of the PhD might focus on generating scientific results but given that most PhD students leave academia (estimates are between 95 and 98%) it is important to develop your whole self.

The Future’s so Bright I gotta wear shades

As Professor Martyn Kingsbury (Head of Imperial Education Development Unit) puts it so eloquently: your PhD is when you move from being a consumer of knowledge, learning what other people have done, to a provider of knowledge, producing data that other people will have to learn. My first experience of this was during my BSc project: I was looking at my squashed flies and feeling a bit uncertain about what the point of it all was when my supervisor came into the microscope room and said: “you see that, the thing you have just done – you are right now the only person in the world who knows that”. And that is what science is about, that flash of discovery, that satisfaction when the pieces of the puzzle fit together, the glow that however briefly you are the only person in the world who knows something. Doing a PhD had some of these moments and now as a lab head, I try to guide others to have them too.

Race for the Prize

The standard metaphor is that a PhD is a marathon not a sprint. But this draws on the wrong sport. A PhD is much more like a football season. It’s about consistency over a longer period, not constantly winning – you can even lose occasionally and still do well. The football analogy can be stretched a bit further over the length of a career, with each year a chance to reset and start fresh. One of the advantages of being in science for a longer time is that you get to see projects through to fruition. The ideas that you have which were initially rejected can be polished up, resubmitted and eventually find a home.

We’re going to be friends

I consider myself incredibly fortunate to work at Imperial, this is fundamentally driven by the people. I have met and worked with brilliant, kind, funny, supportive scientists, without whom this job would not be half as good. This connection began during my PhD and my fellow students now form the nucleus of a collaborative and supportive network that spans from Brisbane to Cardiff. Nurture your friendships.

Don’t Leave

No one ever really leaves Imperial. I did briefly try. For three years between 2008 and 2011, I worked at St George’s in South London. Luckily, I ignored the churlish temptation to say something along the lines of “screw you guys, I’m leaving”, as three years later I was back again – albeit one floor up from where I had been before. The science community in London is quite small, everyone knows everyone. This can be great because the network you build can help you out in all sorts of unforeseen ways. But it does necessitate some care, the person who you complain about one day, may end up being your office buddy the next.

London calling

I spend a lot of time dashing between St Mary’s Campus in Paddington and the mothership at South Kensington for some or other meeting. But this isn’t as onerous as it sounds, as I get to walk through Hyde Park and see the changing of the seasons. Which is just a fragment of the amazing things just on our doorstep. A lot of which is very easy to miss in the daily grind. But make time, go for lunch in the remarkable Art Deco café at the V&A, and if that is too far – go to the physics building for a cup of tea for fantastic views across Hyde park and beyond.

9 to 5

One of the best things about doing science is also the worst. Science is open-ended, fascinating and mostly you get to set the direction of what you are exploring so build on your interests. But this can mean that you can end up thinking about work all of the time, with no defined beginning or end of the day. Which is fine when things are going well. But when the inevitable setbacks pile up, there can be little respite. It can often feel like the best approach is to just do more work. At times like these, stepping away from the bench, taking some time out, for example by going for a run in one of London’s parks can help.

Life happens

In the process of doing my PhD, I met my future wife. While doing my postdoc, we married. When I started my group, I also started my family. And just recently there has been my first lab marriage (not actually in the lab, though I did offer to give the bride away). If you are too busy focussing on the job, you will miss these moments.

When I grow up

It is very easy to look at other people further down the track than yourself and assume they had life mapped out from the outset. This isn’t helped by the endless social media bombardment of success, which luckily didn’t exist when I was starting. Looking back, my career looks fairly linear, but at no point during my PhD did I think I would want to run a research group at the same university. I wrote up and then applied for a whole range of different jobs. In the end I took a postdoc position, mostly on the rationale that I had trained in science for three years, so I ought to see what it was like as a job. Even then I didn’t look much further forwards. I certainly didn’t have a single topic of research I wanted to work on. There is no harm in having a vague plan but being open to opportunities is vital.

Have fun

So in summary, have fun. Take time out, make friends, work to live rather than live to work. This way you will get the most out of your PhD and beyond.

Postscript: I was asked whether anything at Imperial has changed. Beyond my being older, the biggest change has been the space. The buildings have had a massive overhaul in the last 20 years, going from quite tired to shiny and new. I miss the old Holland Club and Southside bars, but I think that is more nostalgia for a time when I could pop out for a drink (or two) after work without having to race home to collect the children.

My ability to predict the future is extremely low, things never quite work out as I imagine them. I honestly do not know what the next 20 (or even 5) years hold. A blend of opportunities, successes, disappointments, tantrums, scientific breakthroughs and scientific dead-ends no doubt, backdropped by a cast of wonderful colleagues and students.

Dr John Tregoning (@DrTregoning) is a Reader in the Department of Infectious Disease. His research focuses on the development of vaccines for respiratory infections, and on understanding why some individuals get more severe disease following respiratory infection.