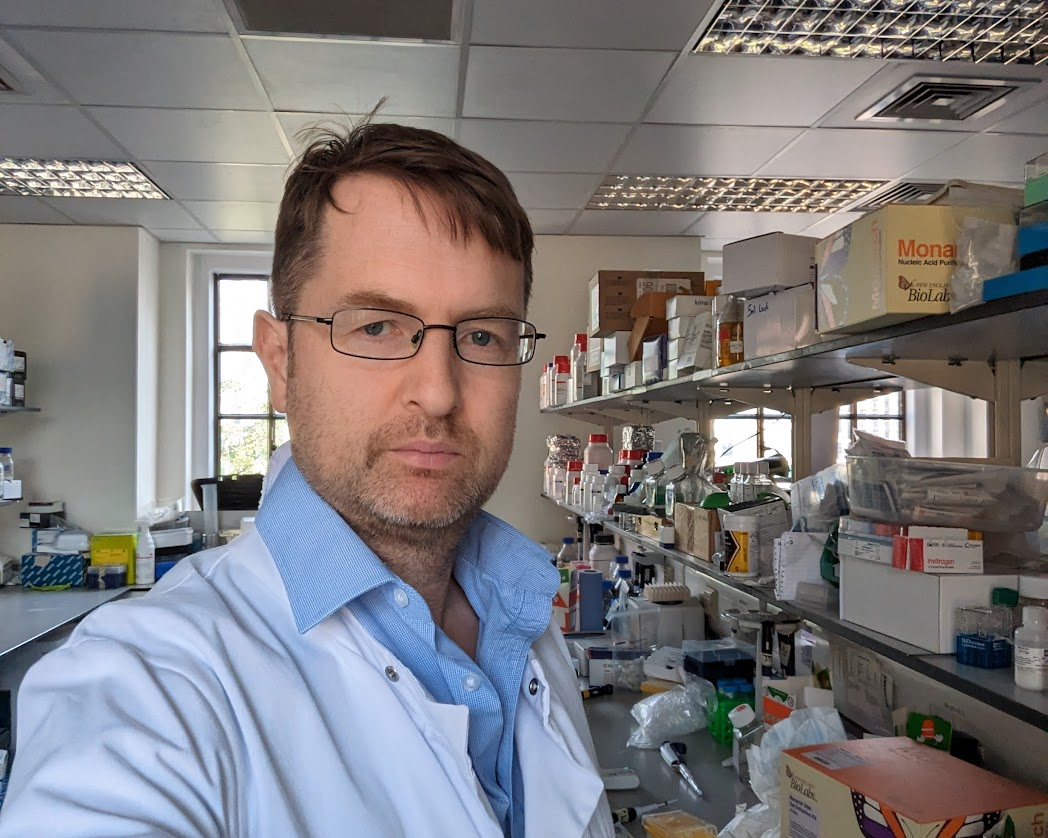

How does a scientist’s journey shape their groundbreaking work? Prof John Tregoning from the Department of Infectious Disease shares insights on his inaugural lecture, “Viruses, Vaccines, and the Written Word,” discussing his career, scientific contributions, and the vital role of collaboration in advancing science.

How does a scientist’s journey shape their groundbreaking work? Prof John Tregoning from the Department of Infectious Disease shares insights on his inaugural lecture, “Viruses, Vaccines, and the Written Word,” discussing his career, scientific contributions, and the vital role of collaboration in advancing science.

One of the milestones of academic life is the inaugural lecture. The origins of this are lost in the mists of time, specifically the mid-1950s at Imperial. It is apparently an opportunity for a new Professor to profess their expertise in an area of science. How this differs from lecturing as a lecturer is a bit unclear; I must admit, I am a bit sad there was no reading test on promotion to reader, I’d have aced that.

One of the key tenets of the inaugural is that it is open to all, providing an opportunity to engage with a wider audience. To support me, Imperial has provided me with seven key facts about inaugural lectures, including the most terror-inducing one: the most viewed lecture has been watched 1.5 million times.

Taking this all in my stride, on 28 May 2025, I am giving my inaugural lecture entitled: ‘Viruses, Vaccines, and the Written Word’. From this title, you should get the impression of the things I work on and what I am going to talk about. There is no specific brief as to what you should lecture on, but I have a few set goals: profess knowledge to the public and smash 1.5 million views on YouTube (two of these are realistic).