Dr Jasmin Cooper, Research Associate here at Imperial’s Sustainable Gas Institute, shares the work being done to model the potential global warming impacts of H2 emissions in possible future supply chains.

Short lived climate pollutants are greenhouse gases which stay in the atmosphere for much less time than carbon dioxide (CO2). Despite this, they are much more powerful than CO2 and can trap as much heat as thousands of kilograms of CO2 on a mass-to-mass basis (Table 1).

Table 1: Properties of different greenhouse gases (Derwent, 2018, Derwent et al., 2001, Derwent et al., 2018, Derwent et al., 2020, Field and Derwent, 2021, Forster et al., 2021, Myhre et al., 2013, IPCC, 2007).

| Greenhouse gas | GWP over 500-year time horizon | GWP over 100-year time horizon | GWP over 20-year time horizon | Lifetime in the atmosphere |

| Carbon dioxide | 1 | 1 | 1 | Hundreds of years |

| Methane | 7.6 | 29.8±11 | 82.5±25.8 | 12 years |

| Black carbon | – | 900±800 | 3,200 (+300/-2,930) | A few weeks |

| Hydrofluorocarbonsa | 435 | 1,526±577 | 4,144±1,160 | 15 years |

| Hydrogen | – | 4.3 to 10 | – | Four to seven years |

afor the hydrofluorocarbon HFC-134a.

In recent years methane (CH4) has emerged as the most important short lived climate pollutant with the IPCC’s AR6 report finding that emissions of it must be cut for 1.5°C or 2°C temperature targets to be met (IPCC, 2021, McGrath, 2021). This is because it is, at present, the second most important greenhouse gas, being responsible for around 30% of global warming to date (McPhie, 2021). It is also the second most emitted greenhouse gas e.g. in 2019 the UK’s total greenhouse gas emissions were 80% CO2, 12% CH4, 5% nitrous oxide and 3% fluorinated gases (BEIS, 2021). As energy systems move away from fossil fuels, hydrogen (H2) could replace natural gas in areas that are difficult to decarbonise through electrification, such as heavy industry and heat.

H2 is a greenhouse gas, but unlike CH4 it is an indirect greenhouse gas. It does not absorb and trap heat but interferes with other (direct) greenhouse gases by enhancing their warming potential (Derwent, 2018). Therefore, in a world where H2 is used in a way akin to natural gas is now, there is the potential for H2 to be emitted into the atmosphere and contribute towards global warming. While there is limited literature available which estimates the impacts of it in the atmosphere, some as-yet to be peer reviewed research suggests short-term forcing from H2 could be higher than that of methane.

Here at the SGI, we have been modelling the potential global warming impacts of H2 emissions in possible future supply chains. When a 100-year time horizon is considered, H2 will likely not impose extra burdens to meeting Paris Agreement goals. However, if shorter time horizons and other climate metrics are considered, the impacts of H2 could be greater, as short-lived climate pollutants exhibit the majority of their warming impacts in the first few years of being emitted. This is an area where more research is needed, as it is important to fully understand the climate impacts of H2 if it is to become a key energy source.

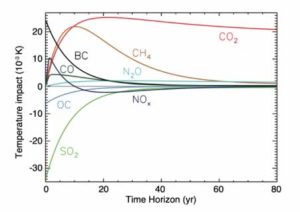

Whilst short lived climate pollutants are important, CO2 is still the most important greenhouse gas because its atmospheric lifetime is long (hundreds of years), and its warming effect is stable (Figure 1). Therefore, when comparing greenhouse gases and creating strategies to tackle global warming, it is important that attention not be drawn away from CO2 i.e. making large cuts to methane emission cannot be used as an excuse to slow down rates of decarbonisation. While short lived climate pollutants are important in the fight against climate change, caution should be used when pitting greenhouse gases against one another based on their GWP, especially GWP over 100-year horizons.

This could lead to unintended consequences either side. For example, a shift away from the importance of CO2 resulting in decarbonisation rates slowing down, or non-CO2 greenhouse gases not being given enough attention and consequentially little action being taken to mitigate emissions.

Overall, the time-horizon considered when comparing greenhouse gases to other another is important but what is more important is the quantity of greenhouse gases emitted. GWP is a useful metric to promote the importance of emissions abatement of non-CO2 greenhouse gases, but its importance becomes less pronounced when emissions are vastly reduced.

References

BEIS. 2021. 2019 UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Final Figures London, UK; Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). Available:’ https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/957887/2019_Final_greenhouse_gas_emissions_statistical_release.pdf

Derwent, R. 2018. Hydrogen for heating: atmospheric impacts – a literature review London, UK; Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). Available:’ https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/atmospheric-impacts-of-hydrogen-literature-review

Derwent, R. G., Collins, W. J., Johnson, C. E. & Stevenson, D. S. 2001. Transient Behaviour of Tropospheric Ozone Precursors in a Global 3-D CTM and Their Indirect Greenhouse Effects. Climatic Change, 49, 463-487. 10.1023/A:1010648913655

Derwent, R. G., Parrish, D. D., Galbally, I. E., Stevenson, D. S., Doherty, R. M., Naik, V. & Young, P. J. 2018. Uncertainties in models of tropospheric ozone based on Monte Carlo analysis: Tropospheric ozone burdens, atmospheric lifetimes and surface distributions. Atmospheric Environment, 180, 93-102.

Derwent, R. G., Stevenson, D. S., Utembe, S. R., Jenkin, M. E., Khan, A. H. & Shallcross, D. E. 2020. Global modelling studies of hydrogen and its isotopomers using STOCHEM-CRI: Likely radiative forcing consequences of a future hydrogen economy. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 45, 9211-9221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.01.125

Field, R. & Derwent, R. 2021. Global warming consequences of replacing natural gas with hydrogen in the domestic energy sectors of future low-carbon economies in the United Kingdom and the United States of America. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy.

Forster, P., Storelvmo, T., Armour, K., Collins, W., Dufresne, J. L., Frame, D., Lunt, D. J., Mauritsen, T., Palmer, M. D., Watanabe, M., Wild, M. & Zhang, H. 2021. The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge, UK and New York, USA; Cambridge University Press. Available:’ https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf

IPCC. 2007. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge, UK and New York, USA; Cambridge University Press. Available:’ https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/ar4_wg1_full_report-1.pdf

IPCC. 2021. AR6 Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Geneva, CH; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Available:’ https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/

McGrath, M. 2021. Climate change: Five things we have learned from the IPCC report. BBC News.

McPhie, T. 2021. International Methane Emissions Observatory launched to boost action on powerful climate-warming gas [Press Release]. Brussels, BE. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_5636.

Myhre, G., Shindell, D., Bréon, F. M., Collins, W., Fuglestvedt, J., Huang, J., Koch, D., Lamarque, J. F., Lee, D., Mendoza, B., Nakajima, T., Robock, A., Stephens, G., Takemura, T. & Zhang, H. 2013. Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forc- ing. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge, UK and New York, USA; Cambridge University Press. Available:’ https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WG1AR5_Chapter08_FINAL.pdf