Dr. Pedro Gerber Machado works as a Researcher at Imperial Colleges’s Sustainable Gas Institute. Pedro is from Brazil and is interested in the sustainable development of energy production, thorough the development of new technologies and the application of policies. In this blog, Pedro talks about the inaction towards renewable energy in the last 30 years and how we need to change the history in order to have a true energy transition.

Dr. Pedro Gerber Machado works as a Researcher at Imperial Colleges’s Sustainable Gas Institute. Pedro is from Brazil and is interested in the sustainable development of energy production, thorough the development of new technologies and the application of policies. In this blog, Pedro talks about the inaction towards renewable energy in the last 30 years and how we need to change the history in order to have a true energy transition.

The definition of “transition” is not the most controversial definitions of all time, probably not even in the group of the 10 most controversial definitions found in the English language, if not in any language. Even so, the concept of “energy transition” seem to be of great controversy and a theme of great debate more and more as we reach the tipping point of climate change, that point in time which changes will be too late to be made. Taking the Cambridge dictionary definition, “transition” means “a change from one form or type to another, or the process by which this happens”.

Energy transition, nonetheless, has several definitions in academic papers, for example:

- A change in fuels and their associated technologies;

- Shifts in the fuel source for energy production and the technologies used to exploit that fuel;

- The switch from an economic system dependent on one or a series of energy sources and technologies to another;

- The time that elapses between the introduction of a new primary energy source, or prime mover, and its rise to claiming a substantial share of the overall market;

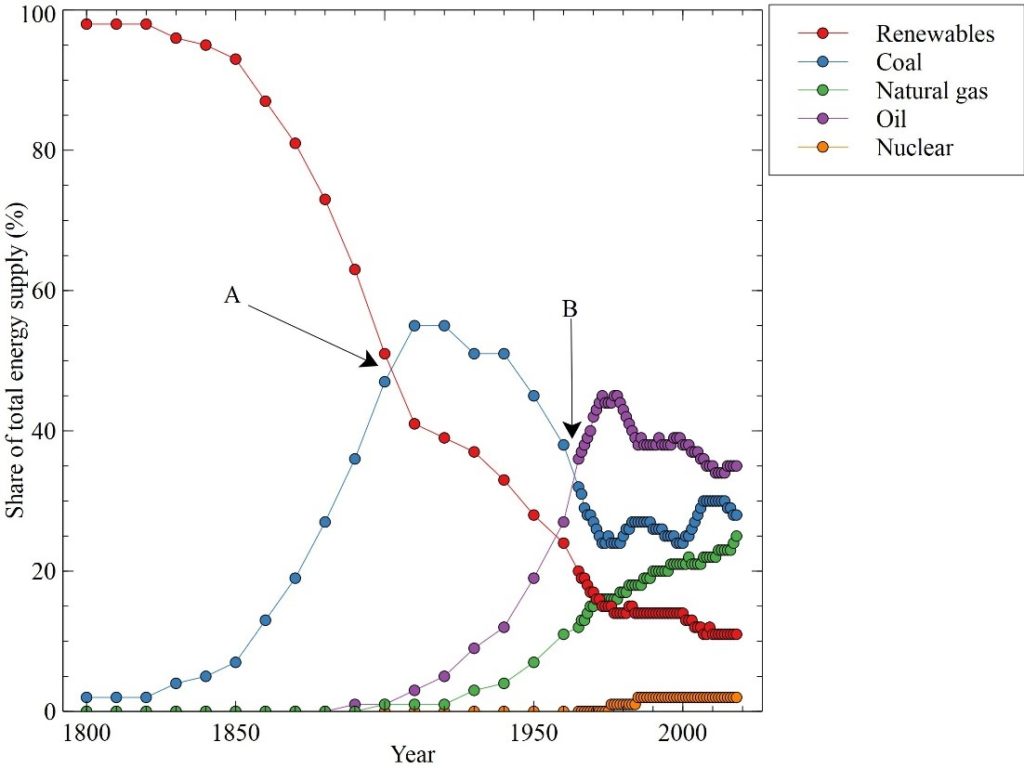

These definitions of energy transition all vary in scale. Scale because they are based on “technology”, which could be a simple technological switch from fans to air conditioning in the US, for example, or from single-fuel cars to flex fuel cars in Brazil. On a macro scale, where there are big changes in energy systems on a national or global level, academics use the time of introduction of coal and crude oil in the energy matrix as examples of “energy transitions”, as seen in figure 1.

The arrows show the moment where the so called “energy transition” happened in the world. In a simple way, the transition is said to have occurred from biomass to coal in in the late nineteenth century and from coal to oil in mid-twentieth century. It seems like a true “transition”, in which biomass reduces, coal increases and later on coal reduces and oil increases.

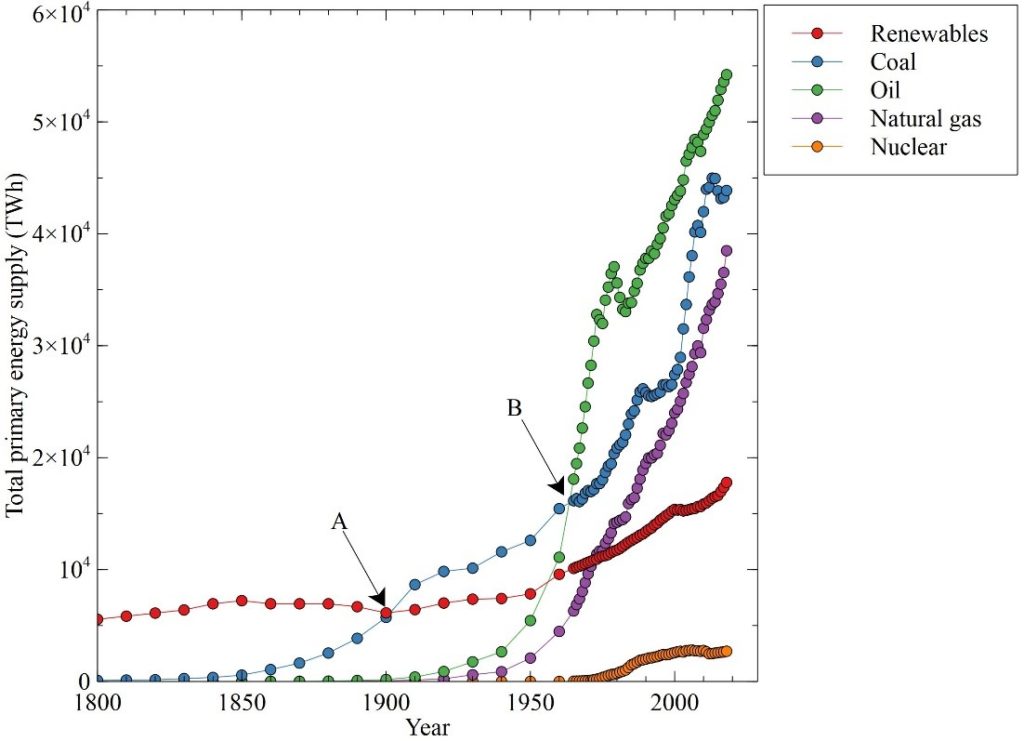

Let’s now take a look at the absolute primary energy supply in the line graph, with arrows showing the same moments in time when the “energy transition” took place.

When it comes to total primary energy supply, there was no “transition” (based on the dictionary definition), but instead what happened was a mere “addition”. In both moments there was no “change from one form or type to another”, simply because the other sources are still around. Traditional biomass was still around long after coal entered the energy matrix (and still exists today) and the same goes for the point when oil was introduced, there was no transition there, only an addition, since coal is still rising alongside oil, not falling.

Future transitions

More important than determining if what the world has gone through in the past was a “transition” or an “addition” is what is coming in the future and by the future we mean what is happening now. Transitioning away from our current global energy system is of paramount importance, since its negative environmental and social impacts are of global proportions and we are fast reaching a point of no return.

But it is also important to identify both the similarities and the differences between past and prospective transitions. A crucial issue is that, during past energy additions, both consumers and producers benefited from the new energy source. This is mainly due to lower fuel prices and the new developments in mechanics taking place during that those times. Whereas these private economic and financial benefits are not as obvious for low carbon energy sources and technologies, due to higher prices, generally. Moreover, the introduction of clean, low carbon energy sources has to take place in a real “transition”, and not repeat the same additions the planet has seen in the past.

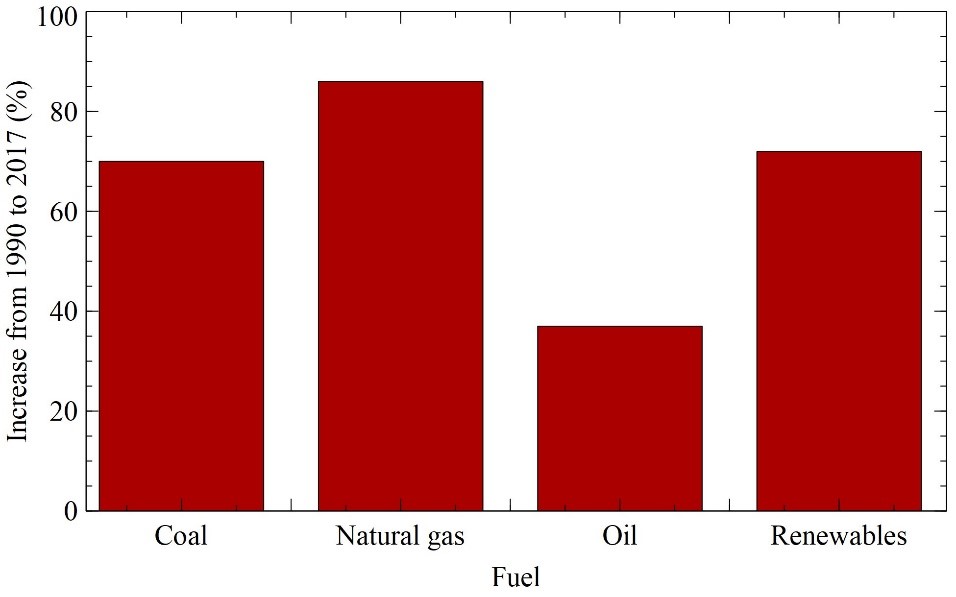

The bar chart (Figure 3) shows the relative increase of each energy source from 1990 until 2017. This is an important period due to the global increase in environmental concern over these past (almost) 30 years. There was Rio, there was Kyoto, there was Paris and still fossil fuels increased in production.

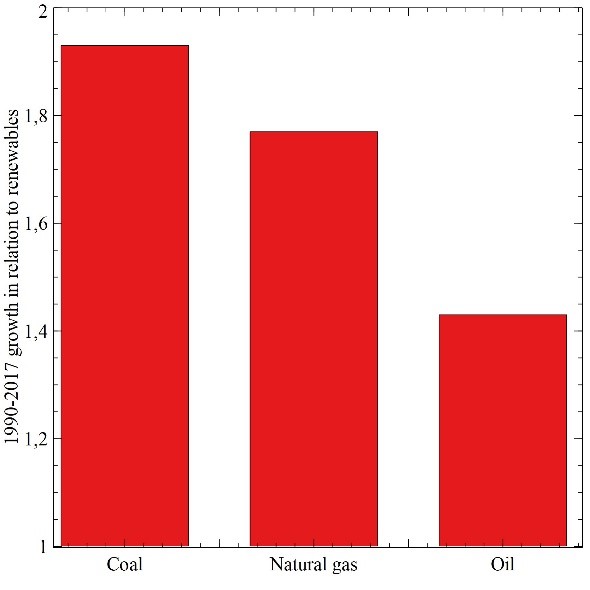

The problem, however, is worse when we see that the increase of fossil fuel has been, in absolute terms, higher than renewables in Figure 4.

What we see is that, for every 1 unit increase of energy from renewables in the last (almost) 30 years, coal increased 1.93, natural gas 1.77 and oil 1.49. In a world that needs to fully transition to renewables, this is not a good picture.

Unfortunately, this is a repetition of the past. Renewables are just being “added” to the energy matrix, while there is no reduction from the fossil side. This is incompatible with the desired climate change mitigation actions. To have a genuine transition, renewables need to increase in a proportion such that fossil fuels decrease in supply. Only then will the energy transition be an authentic out-of-the-dictionary transition, and not a trifling addition.

Note:

- Figure 3: Graph data is from Energy by Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser

- Figure 4: Data is from IEA.