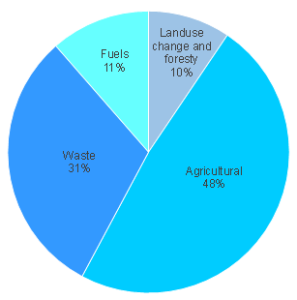

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the waste sector are primarily composed of methane (CH4) released from landfills. Biodegradable wastes such as food, garden waste, manure, paper and cardboard emit methane during anaerobic decomposition in landfills. In our latest blog, SGI emissions scientist Dr Semra Bakkaloglu explains some of the key findings from her newly published paper into emissions of CH4 from biowaste.

We know that CH4 is around 28 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide (CO2) over a 100-year period (IPCC 2021). So, reducing CH4 emissions – from all sources – is critical to keeping global median temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius. In the UK, the waste sector is the second largest CH4 emitter after agriculture, so waste sector emissions deserve significant attention if we are to achieve the UK’s net zero targets.

The UK biodegradable waste strategy aims to divert progressively more waste from landfills into anaerobic digestion or composting facilities for recycling. Recent studies (Gua et al. 2020, Bakkaloglu et al. 2022a, Cusworth et al. 2020) indicate that anaerobic digesters and composting facilities can be a significant source of CH4 emissions, and our latest study aims to evaluate the UK’s biowaste strategy to better understand future CH4 emissions.

The UK biodegradable waste strategy aims to divert progressively more waste from landfills into anaerobic digestion or composting facilities for recycling. Recent studies (Gua et al. 2020, Bakkaloglu et al. 2022a, Cusworth et al. 2020) indicate that anaerobic digesters and composting facilities can be a significant source of CH4 emissions, and our latest study aims to evaluate the UK’s biowaste strategy to better understand future CH4 emissions.

We use the term biowaste in this study to cover food and garden waste, because the broader term – biodegradable – encompasses a wider variety of wastes such as manure, sewage sludge, paper, cardboard and more. The objectives for our research were to compare the environmental impacts of biowaste treatment in the UK and to assess the effect of CH4 emissions. We considered four different waste treatment methods anaerobic digestion, composting, incineration, and landfill), as well as seven different scenarios for waste in various ratios treated using current and future waste management technologies. Full details of those scenarios are explained in full paper.

The four biowaste treatment methods assessed: anaerobic digestion; in-vessel composting; landfill; incineration with energy recovery. The dashed line indicates the system boundary and blue text indicates recovered resources.

In our latest study, we combined mobile CH4 emissions data for anaerobic digesters (AD) – rather than relying on the default emission factors for life cycle assessment (LCA). Approximately 19% of biowaste in the UK is currently landfilled, while 38% is incinerated. Of the remaining 53%, the waste strategy set a target for AD of 15% in 2020. It is reasonable to assume that 15% of biowaste is sent to AD and the remaining 28% is sent to the composting facility. Combining the mobile methane emissions from AD and composting facilities, we can estimate that current annual UK average methane emissions are approximately 58.2 kilotonnes.

If we sent 90% of biowaste to AD and 1% to landfills as a strategy for the reducing landfilled biowaste by 2050, annual emissions would decrease to 30.3 kilotonnes. Therefore, sending more biowaste to AD can reduce emissions, but if we want to achieve net zero emissions from the waste sector, remaining emissions must be offset. Therefore, we recommend that future UK waste management policies should also focus on eliminating fugitive emissions from treatment technologies, especially AD, in order to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.