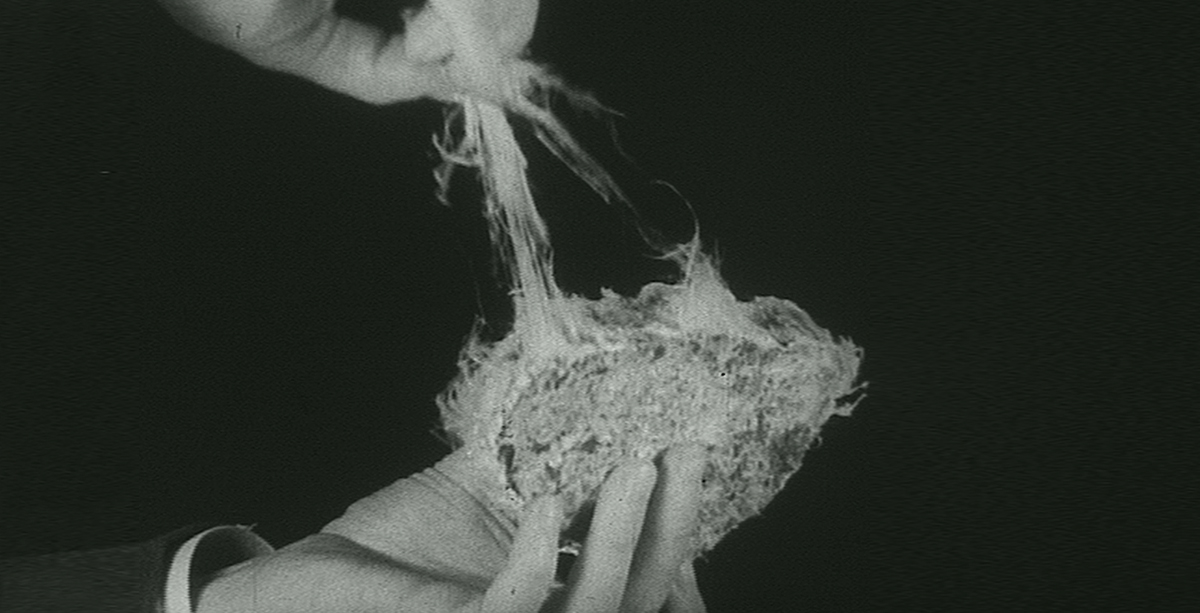

An eye-opening account by Professor Sir Tony Newman Taylor on how asbestos has gone from ‘magic mineral’ to deadly dust that can cause mesothelioma.

An eye-opening account by Professor Sir Tony Newman Taylor on how asbestos has gone from ‘magic mineral’ to deadly dust that can cause mesothelioma.

Public awareness of the hazards of asbestos can be dated to the period immediately following the death of Nellie Kershaw aged 33 in 1924. She had worked during the previous seven years in a textile factory spinning asbestos fibre into yarn. She died of severe fibrosis of the lungs. The pathologist, William Cooke, who found retained asbestos fibres in the lungs, called the cause of death asbestosis. Nellie Kershaw was not the first case to be reported of lung fibrosis caused by asbestos. Montague Murray in 1899 had reported the case of a 33-year-old man who had worked for 14 years in an asbestos textile factory. He had died of fibrosis of the lungs which Montague Murray, also finding asbestos in the lungs, had attributed to inhaled asbestos fibres. The patient had told Murray he was the only survivor from ten others who had worked in his workshop. (more…)