Four Imperial researchers recount their experiences of volunteering at one of the mega-labs built to scale up COVID-19 testing in the UK.

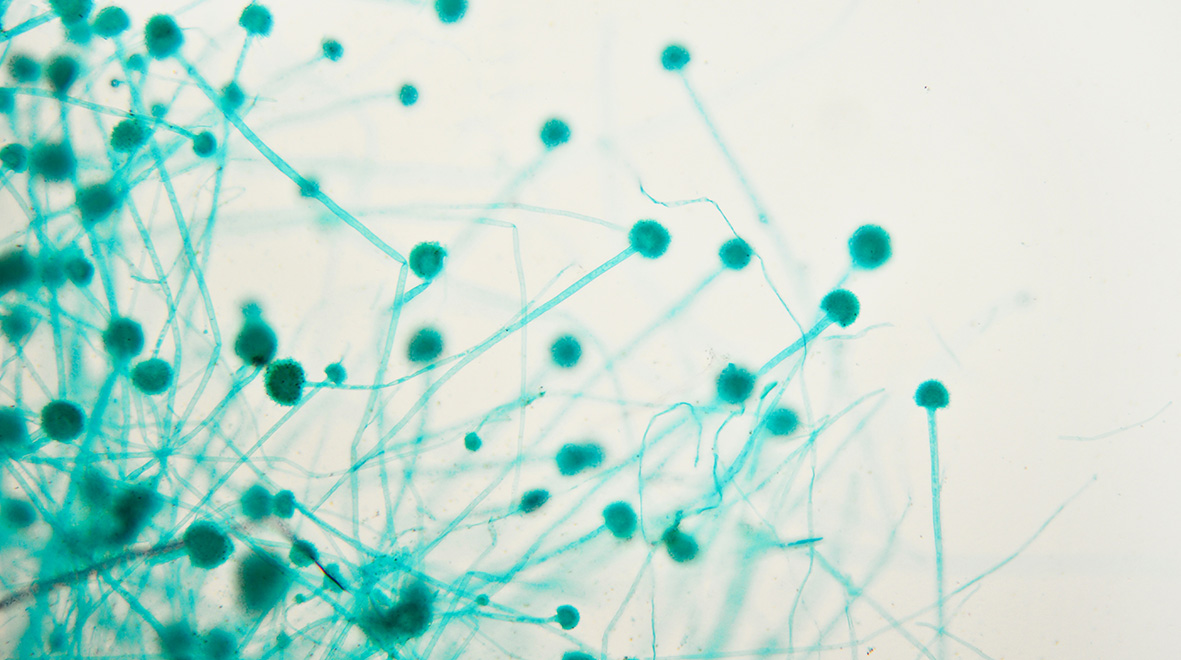

Since March, the UK Biocentre laboratories located in Milton Keynes has become one of four Lighthouse Labs (the others are in Glasgow, Alderley Park in Cheshire and Cambridge) – the largest network of diagnostic testing facilities in British history. Every day the team process and analyse around 30,000 swab samples from across the country to test for the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19. They use a combination of manual processing and high-throughput robots to inactivate the viral samples, extract the RNA and analyse them with a technique known as quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to detect the presence of the virus.

The UK Biocentre labs were uniquely placed to help in the testing efforts, as in normal life they are usually home to around 30 staff processing and archiving clinical samples from hospitals around the UK. 200 volunteers across academia, civil service and industry answered a call to support with COVID-19 testing, including several PhD students and postdocs from Imperial. As their secondments draw to a close, we speak to some of the volunteers to hear about their experience: (more…)